From Panama to Pandemic: Una Vida de Austeridad

Para leer esta historia en español, haz clic aquí.

In March 2020, the pandemic hit, the United States shut down, and I breathed a sigh of relief. My mom could finally quit her job as a Stock Associate at Walmart, where she worked in upstate New York. She seemed just as scared as me, especially as an older asthmatic. And though she had been dismissing my attempts to get her to quit, this, I thought, would finally give her an opportunity to step away from her twenty-year career with grace. I strolled into the talk with newfound confidence. I wasn’t going to ask her “if” she was going to retire anymore. I asked her, “when in the next week are you going to retire?”

I had been trying to convince my mother to quit her job ever since I began to sense that her health was getting worse. I had assumed that, everyday, at five in the morning, she had woken up for her shift, shrugged, and figured, why not? After so many years, what’s another one? I had tried to challenge her rhythm, her endless inertia, her unchangeable schedule of working. But every time, she batted away my arguments, assuming me to be too naïve to understand.

“I have to keep working,” she would say, cutting me off. She doubled-down on this defense even after admitting that, on a camping trip with my father, she had fainted. One day, I caught her shaking atop a small step stool as she tried to put back a dish in the kitchen cabinet.

“Please, mom,” I pleaded with her. “Let me do the hard work.”

“Christian,” she laughed. “Do you know how many ladders I have to go up and down every day?”

Sure enough, later that week, finding her in the Personal Care section at Walmart, I watched in horror as my mother rolled her metal ladder to various shelves. This was a new development: in all her years of stocking at Menswear, she had never needed to use the metal ladder. She stopped at one point, seemed to sigh, and crept up the steps to balance a box of Just For Men’s along a line of other hair dye. I imagined her missing just one of these steps, just once, in one of the hundreds of opportunities she had every single day, and crashing below, a fifty-nine year old woman disposed of for the sake of Walmart.

I started to pry more in my conversations about her work, asking about her risks, expecting her to change her tone, to finally cede ground, to give me a final date and for us to reflect over her time at Walmart in a peaceful, accepting light. But as much as she complained, accepting the difficulty of her work, she refused to entertain the idea of quitting. We seemed to approach the importance of her job from two very different viewpoints.

I hoped things would be different because of the pandemic. I hoped that, finally, our viewpoints would converge and my mother would quit. Cases started to appear in places close to my mother’s Walmart. Facts pointed to the risk in being anywhere near a potential carrier of the virus, and lots of potential carriers would be entering Walmart.

I mentioned this all to my mom. I used my sister’s new job and salary as a bowtie to my mother’s resignation. “We’re not in austeridad anymore!” I joked, referring to my mother’s past when the Panamanian government restricted resources. My sister could support my mother; my mother, always aware of money and her access to it, could lean on the success of her children, even if, by this point, my father could support both of them with his Army pension.

The talk ended. My mother laughed and shook her head.

She already knew about the facts and the danger of infection.

She knew how easily it spread because one of her coworkers had already gotten sick from working in the store.

She was going to keep working.

She had never considered quitting, not even in a pandemic.

When my mother first started her job at Walmart, around 2000, we celebrated. She took the job on with pride. She had arrived in the United States in the early 90s, but as an immigrant, her credentials from Panama hadn’t counted for much. And even though documentation wasn't an issue—my father is a white man, and my mother naturalized early into her new life in the U.S—she frequently needed to work odd jobs, like dishwashing, and her employers paid her under the table.

Walmart, though, was different. Its buildings stood, immense, as a literal and figurative symbol of the American landscape. Everyone associated Walmart with the United States, and maybe someone like my mother could be associated with this country by working at Walmart. Plus, this job would be her first time on an official bankroll, her name recognized on checks and contracts and paperwork.

Before long, when I was about nine, I started to accompany my mother to work on my days off from school. I would help her configure prices through a handheld device that tracked product and quantity. A certain tranquility accompanied her assigned department, Menswear. It always seemed in perfect order because of my mother, and the folded clothes and always-vacuumed carpet flooring reminded me of home in a small way. Few male customers seemed to ever be in her section, and those who did wander over seemed uninterested in asking questions, so they simply ignored my mother.

But each time I went with her to work, a new worry grew in my mind: what if someone disturbed this peace? What if someone did ask her a question? My mother, brown and short, speaks English with a noticeable accent. I worried about how others would treat her if they saw her as "different."

My worry only worsened as I outgrew my mother’s supervision and stayed home alone. Were all the men I never saw in Menswear going to appear now that I, her advocate, was gone? Were the customers going to treat her well? I started catastrophizing and thinking that my mother was going to come home one day, crying, mistreated for being an immigrant.

Instead, the opposite happened. Where I expected horror stories, my mother surprised me, more and more, with positive encounters at work.

“I tell him, 'how do you think I know? I work here now for three years!'” she said once when a man questioned her knowledge about where to find a car accessory, probably assuming that she wouldn’t know since she worked in Menswear.

With each passing year, she gained more confidence in her role. After about five years, a new manager started working there and asked for my mother’s help to better understand the store. My parents joked that she was the true “boss” of Walmart since, by that point, she knew so much about the formal rules of the corporation in addition to the tendencies of other associates.

Counting on her expertise of Walmart seemed like another way in which my mother claimed her own corner in her new country, one in which she could push back against Americans who might argue against her place here. Working everyday didn’t just give her something to do with her time—it gave her a sense of belonging. It gave her a sense of immense pride.

*

As a kid, my mother once shouted at me for tossing a few pennies out into an open parking lot—just spare change, from candy bought at the store. As she heard the pennies cling together in my hand and then tap against the pavement, she jerked her head toward me.

“If you knew how I grew up, you would never do that,” she said.

This attitude permeated her whole life.

The only time my mother’s title as Stock Associate might have changed was when, in 2009, after close to ten years in Menswear, she was offered a promotion. During this time period, my mother’s stress fixated on this debate: take this promotion to Department Manager and make more money, or take less money and save herself the headache? My mother seemed to agonize in considering the new duties associated with a manager position: working longer hours, overseeing big-picture operations, and supervising other coworkers, many of whom were native English speakers and native-born citizens.

Finally, after suffering alongside my mother for weeks, listening to her vent at the dinner table as she sized up the job offer, I worked up the courage to ask her the one remaining question. How much was the raise?

“Oh,” she said, as if this were an inconsequential detail. "Fifty cents."

Fifty cents per hour separated her official title as a Stock Associate at Menswear and her potential headache as Department Manager.

Fifty cents had caused this tremendous dilemma.

Having only worked at one job by this point, at the age of 16, I was unsure if I was misinterpreting the importance of fifty cents per hour. The math is easy—my mother would earn twenty dollars more per week as a manager. I wasn’t sure if I just didn’t know how much twenty dollars was really worth at my age. Otherwise, why would my mother consider the promotion?

How could I have possibly understood my mother’s dilemma? I had no conception of her upbringing.

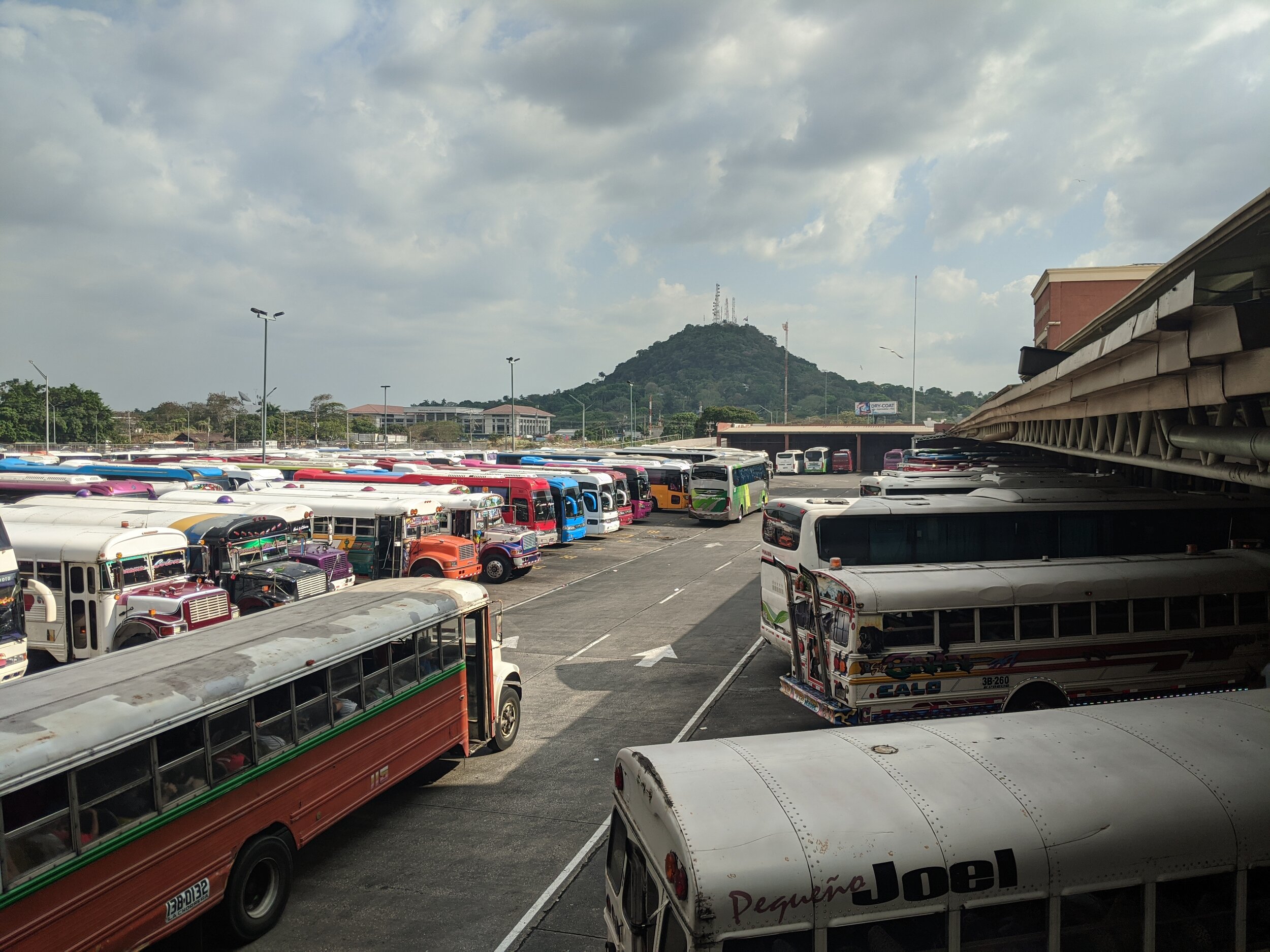

Last year, almost a full decade after having first been subjected to my mother’s debate over her promotion, I traveled to Panama to unearth some of our family’s history. Growing up without any of my aunts and uncles from Panama around, I didn’t know much about life there. I hungered for firsthand information—sights, sounds, smells.

Soon after my arrival in Santiago, a mid-sized city and the capital of the province of Veraguas, I traveled with my family to my aunt’s finca near Santa Fe. I was immersed in orange trees, hundreds of them, so thick with ripe fruit they made the landscape glow. Pride feels woven into the character of this place, not only because it showcases how bountiful and beautiful Panama can be, but because it’s the rumored homeland of Urracá, legendary indigenous chief, and the real homeland of Omar Torrijos, a leader who, for some, came to symbolize peak populism in his social reforms and pride in being from the interior—not Panama City.

We’d come to pick these oranges from the finca to sell in the city. Covered in the mandatory outfit of orange harvesters—long sleeves, pants, a baseball hat for me, a traditional sombrero pintao for the day laborers—we marched out into the grove in pairs: my aunt and me, my two cousins, and the two day laborers. One person would climb the orange trees and drop oranges to the other, waiting below with the nylon sack nets.

We worked nearly all day to fill about twelve sacks total, or two per person. By the time we finished filling the sacks, I could have collapsed. We still needed to bring them all the way back through the jungle and to my aunt’s truck.

My spine cracked as I squatted down to load a sack onto each shoulder. My aunt beckoned me to move faster while she navigated the muddy path with ease. We approached a stream and, while I considered how we might build a path of rocks over it so that we could cross, the rest of the group simply jumped in, wading through water and mud with the backbreaking sacks held high. Of course. What was the simplest way to cross the stream? Well, crossing it.

By the time we made it back to Santiago, it was night. I had slept on the long, two-hour drive back, welcoming a chance to relax. But our adventure in picking the oranges was only part of the day’s job: now, we had to sell them.

We posted up at my abuela’s place, just off one main road, and spread out, advertising the fresh oranges to neighbors and strangers alike. My aunt, savvy, strong, both having picked the oranges and overseeing the sale, convinced one neighbor right away to buy and ushered me to fill up a sack. I obliged, summoning the last of my strength to deliver the sack, and waited nearby the entrance to the neighbor’s house as my aunt secured the deal.

Finally, after having suffered alongside my aunt, working all day to fill these sacks, testing the limits of my body—proving myself a city boy, or a yeye, as Panamanians put it—and wading through water, I’d reap the reward. How much was my aunt charging per sack? How much was my labor worth?

Two-fifty.

Two dollars and fifty cents for bouncing from one branch to another as they cracked under my weight, threatening me with a long fall down to the jungle floor. Two-fifty for steadying my buckling knees as I dug my feet into the muddy route back to the truck.

We would earn thirty dollars for the entire day of work between six people. Later that evening, when all the oranges had been sold, my aunt tried to hand me my share of the wages. I shook my head, saying that the chance to spend time with them was enough.

All of a sudden, that twenty dollars extra a week took on more value, and I understood more of why my mother had agonized over accepting the promotion.

My mother ended up declining the promotion. After that, she left Menswear, and while she moved around various departments, she never changed her fundamental job description of stocking shelves and helping around the store.

The peak of infections was expected to arrive in a few days and my mother and I had not reached a resolution. I brought up the point of quitting again and my mother countered by mentioning her coworkers.

“What about them?” she said. “They have to keep working.”

I thought at first that she used them as a shield of sorts, hiding behind them in a way that allowed her to sidestep her need to defend her job. In my mind, she had little left to excuse how she put herself in peril for the sake of an hourly wage—I had already brought up my sister’s willingness to support her, after all.

“Please, mom,” I begged. “We never ask anything of you. What’s more important? Your health? Or your job?”

“Tú sabes que uno tiene sus amistades,” she said. As you know, one has their friendships.

I pictured her amistades the same way I picture most work friendships—held at arm’s length, nice for the sake of maintaining a positive work environment.

“You know, they can’t take off,” she continued.

“So they’re just going to keep working? Even during the peak?” I asked. As soon as the question left my mouth, I felt stupid for asking it.

“Yes, Christian. They don’t have the money.”

Something about this particular defense gave me pause. She seemed caught up in the moment, revisiting memories of these same friends in a way that made me realize that, perhaps more than the pride or money, she really was just thinking about…friends. Amistades.

I remembered how, one day, around 2010, my mother had asked me to dress up for a barbecue at her co-worker’s place. She had been mentioning some of her coworkers in casual conversation for a while, recounting funny stories of how one of them stood up to a customer, for instance, or how they pranked each other in lighthearted ways. Little by little, she had clarified these coworkers into names: Billy, Martin, Rosa. But going to hang out with these coworkers outside of work was a new development for my mother. She had never had “friends” in this same sense.

Salsa blasted out of huge amps placed around a grassy lot. The backyard was small, condensed for this condo, but cozy. A grill, popped open, sizzled with chicken and veggies. On aluminum trays, I spotted food similar to my mother’s cooking: arroz con guandules, ensalada de papas, pernil. As a teenager, I bee-lined for the food, both being eternally hungry and wanting to avoid conversation with my mother’s friends. But, plate in hand, mouth full, my mother still made me come over.

“Billy! Este es mi hijo, Christian.”

As I shook Billy’s hand and moved to the next coworker in the line of friends to meet me, I noted the significance of my mother’s community. The names from before—Billy, Martin, Rosa, among others—came to life. These friends were brown, too. These friends spoke English with non-native accents, too. These friends, like my mother, were immigrants, having come from different countries.

The only other time I had seen my mother that animated was in Panama. Speaking in her native Spanish, she thrived in conversation, socializing like a new person. The quiet, withheld woman I knew gave way to a new, boisterous Doris. This Doris had put aside a whole life of this happiness—comfortable in her own culture, boisterous at parties held with her own family—for the sake of a new life in the U.S.

Another day, circa 2014, I came to visit my mother at work. I was back home visiting from college. I hadn’t had as much of a chance to catch up with my mother and didn’t know as much about her work life—were her old friends still around?

Business was slow, and the associates seemed to be able to loosen up and socialize under the guise of work. My mother, seeing me, led me through the aisles of the store, introducing me to coworkers along the way. The old cast had mostly given way to a new one, though most were all people of color.

“This is my son, Christian,” she said, and at my mention, her coworkers lit up in a way that told me that my name had come up many, many times in the past. To some of her coworkers, with whom she exchanged quick moments in Spanish, I said, “mucho gusto,” making them smile.

“Ah, ¡pero él sí habla español!” ––“He does speak Spanish!”

The animation returned. My mother sprung into new form, lively, smiling as she mixed in Spanish with English and addressed one coworker after another on her tour of the store.

“Billy!” my mother said as we neared him, excited to get his attention. “Este es mi hijo, Christian.”

He was just as I remembered him. He had a certain swagger to him. I tried to mention that we had already met, stuck in this logical inconsistency of the moment, of how all of this had already happened at the barbecue years ago. But, as Billy smiled, offering his hand, I resigned to let the moment unfold. In that moment, seeing my mother’s excitement at introducing me to a friend, and seeing her friend’s excitement at her excitement, almost, a sense of community and support distilled in my new introduction, I remember catching a glimpse of just how much my mother’s job meant to her.

These were the friends, the Latinos, who had no other option but to work. I imagined my mother taking a convenient leave-of-absence, a resignation, while a pandemic highlighted the inequities among people of color and class in the United States. Would my mother cherish that same privilege to set aside her health? Or, I thought, my mother still lost in her recollection of her amistades, would my mother just feel like a traitor?

I began to understand that so long as her friends continued to work, so would she.

My faultless arguments were meeting an immovable object. My blinding love was meeting an unstoppable force. My mother would not give up her corner in America. My mother would not give up her small measure of autonomy. My mother would not quit her job.

My mother compromised with me. Not out of agreement with our points and argument—she compromised out of consideration for how much the situation was stressing my sister and me. This compromise involved her taking two weeks off, sanctioned by Walmart, in addition to taking off a week from her own vacation time. This would, hopefully, allow her to bypass the peak in New York. Naturally, this pained my mother as she checked in on her coworkers who had not saved up vacation time in the same way.

Then, my mother returned to work. The pandemic, of course, still raged.

While my mother worked stocking shelves in an infected Walmart, I zoomed. I joined Zoom Happy Hours; I attended Zoom class. The real world faded before me and I gained an uncomfortable familiarity with the inside of my apartment. I balked at the idea of going outside, even if just for a walk. Going outside, to me, seemed tantamount to infection.

I chose to disengage with my mother: numb, hurt, I viewed my mother’s stubbornness as a form of spite. Though I comprehended the conclusions I had arrived at on a logical level, appreciating my mother’s agency and her need to work out of pride, independence, money, and community, that logic faltered in the face of the imminent fear that my mother would get sick. I catastrophized again, returning to that child form of myself that asked, everyday, “did someone go up to you at work? Did anyone ask you a question?” Now, though, I thought over a different question: “was everyone wearing a mask? Did someone get near you?”

But I didn’t ask her these questions, disappointed in myself for having failed to save my mother from the virus and hurt at her inability to listen to my needs. I didn’t want the victory of an “I told you so”—I just wanted my mother to be safe. Or, maybe, torn, I wondered about validation of my viewpoint, one that prioritized self and security over friends and community. Was I in the wrong for not considering her amistades more? For not remembering that boisterous vision of my mother, alive and happy at work?

Why was my family stuck in a dangerous either-or scenario at the hand of Walmart? Why was my family breaking their backs over oranges and a handful of dollars? Why were the Latinos working with my mom stuck at a Walmart during a pandemic while everyone else—including me—worked from home? The question brought me all the way back to why my mother first took the job with Walmart and why she had stayed for twenty-plus years, and these types of questions have stayed with me all my life.

In contrast to my mother, the white people in my life have always maintained positions of power, starting with my father: the one whose career moved us to New York in the first place, whose career mattered most, with the most potential in supporting our family. My mother’s longtime manager, Todd, was a white man. Thinking of my mother has always emphasized the types of structures that keep this kind of contrast consistent, where those like my mother and her friends work for Walmart and those like my father work managing them. On a practical level, this type of understanding of whiteness and access to success in the world clarified why my mother might have left everything behind in Panama for a life in the U.S. Of course, there are just fewer opportunities for people like my mother, and they’re driven into the same types of jobs, racialized into blue-collar opportunities that pay poorly.

I considered my aunt, selling oranges, taking me around Santiago in her pickup, telling me, “hay que buscar el real donde sea,” referring to the old Panamanian currency of reales—“You have to look for money wherever it might be.” Did the same apply to white men? Would this search for money always involve working jobs that might endanger the lives of people like my mother?

Before I had left Panama, on the same trip when I had sold oranges, my aunt had confided in me that she needed multiple surgeries, despite already having had many. She pointed to her knees, creaking under her, and her hips, as she canted to one side, always limping toward the end of the day. And yet, she had hiked through the same jungle, climbed the same trees, and crossed the same creek in our journey to collect oranges.

Her hustle for money was literally tearing her apart. And, in this light, I regretted thinking of my aunt as savvy and strong, because I wondered if she’d trade in those qualities for a healthier body, for more money, for a better way to make money. I wondered if the thought trap of considering brown women as hard workers only continues to set them up to be torn apart.

One day, finally, several days after my mother returned to work, my father sent our group chat a photo.

My mother wearing her mask, thumbs up, alive.

She assured us that she was okay: she kept her distance and told customers to stay six feet away, and, surprisingly, she was supported well by her manager. She also recounted lighthearted stories of how her coworkers shared in the experience of battling the pandemic surge—how one coworker ran away from a customer who refused to keep his distance, for example, like fleeing a zombie. I winced with each one of these stories, anxiously awaiting when one would account for her infection.

But she stayed healthy.

Later, removed from the imminent fear of the peak, having endured alongside these coworkers, my mother seemed to recap the time with a sort of nostalgia. I wondered if she and her coworkers grew closer from their shared journey while I soured away in my solitude, safe, but separated from my friends and coworkers by a screen.

So what if she would have quit? Wouldn’t she have continued to have the opportunity to keep in touch with friends? Couldn’t she have dropped in to spend time with them? Couldn’t she continue to go to barbecues, post-pandemic?

The entropy of life seems to pull us apart from close ones and friends. I don’t know if the air about their friendships would have been the same. I imagine the stories they might have told in the break room—the same gossip den as replicated in mainstream media—and I imagine the importance my mother places on the opportunity to share in the telling of these stories, in real time. I still feel conflicted about Walmart. Rationally, the advocate in me fights for relentless critique of the store. On the other hand, I’m happy my mother finds community in her work. But why must community come at the expense of money, or health, or literal safety? I don’t doubt that society is moving in a more positive direction in addressing racism and class inequality, but thinking of my mother makes me see this movement in very, very slow motion. The pandemic, for much as it has changed our lenses of how we view our society, seems inconsequential in stopping the same systems from hardening—the ones that tear apart brown bodies and shrug at the idea of my mother’s health.

Chris Kubik Cedeño is a Panamanian-American writer and first-year fiction student at the Rutgers-Camden MFA program. His writing can be found in Preachy, Porter House Review, and more. Find him on Twitter at @ckcwrites.