Kahlo And Amaral: Artistic Renderings of White Feminism in Latin America

Leer en español.

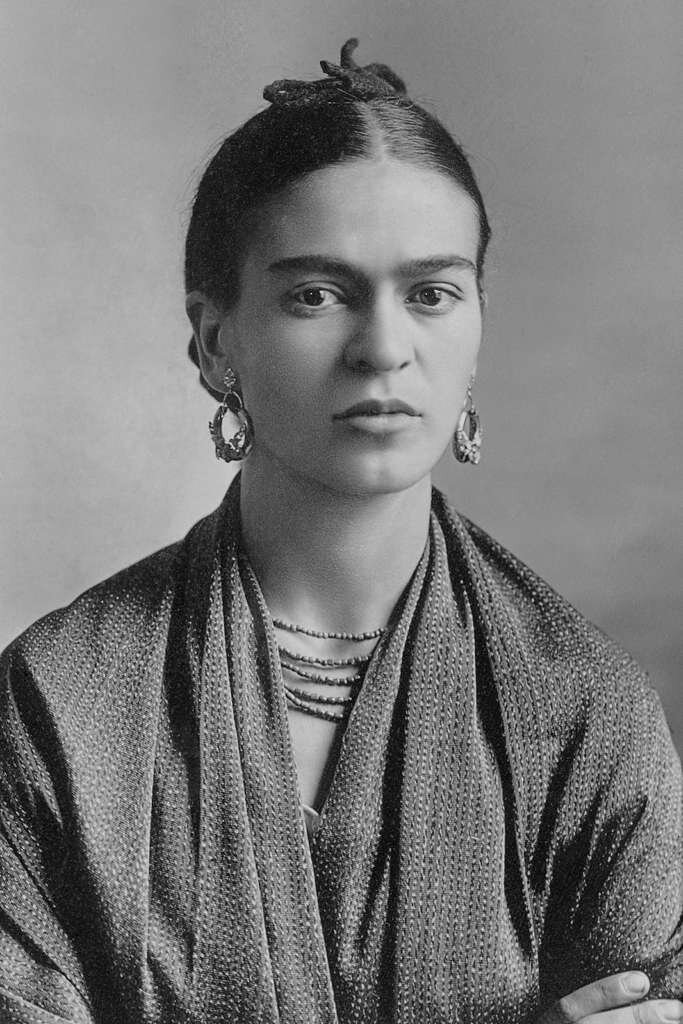

Tarsila do Amaral and Frida Kahlo were two Latin American juggernauts of modern art. Amaral’s dedication to visual primitivism and Kahlo’s surrealist Mexican imagery ushered in a Latin American renaissance that laid the foundation for future generations’ conceptualizations of race, class, and nationalism. Indeed, they rewrote the preconceptions of femininity within their respective chauvinistic societies. However, both women's lives were heavily influenced by the economic classes that they were born into and the ethnoracial admixtures that provided them with the social currency to be embraced into the artistic aristocracy. This piece is not intended to be an anachronistic critique, rather a robust review of two historical figures who represent white feminism’s continued influence in Latin America and about how Amaral’s and Kahlo’s “celebration” of the indigenous and Black identities of Brazil and Mexico was, in fact, a mode of cultural appropriation.

Authors’ Note: Dalí Adekunle and Fernanda Senger became friends during the pandemic, when they began to converse every week to practice their second languages. The conversations flourished beyond English and Portuguese language conventions, current politics, healthcare, and art education. They decided to share some of the insights they exchanged on Frida Kahlo and Tarsila do Amaral—two long cherished but challenging figures. Like Frida and Tarsila, Dali and Fernanda found similarities in their own life paths and common ground in many viewpoints despite their distinct geographical backgrounds. Dali is a black Nigerian-American woman interested in multicultural health communications. Fernanda is a white Brazilian woman interested in art history and education. Both Dali and Fernanda currently live and work in New York City.

Dali: Fernanda, I’m so excited to be having the opportunity to be speaking about the lives and legacies of these two artists with you. Many are not familiar with Tarsila do Amaral’s work, could you give me a brief introduction to who she was and where she came from in the Brazil of the early 20th century?

Fernanda: Sure, it’s a great pleasure to share some of the ideas that have been instigating us lately. First of all, what comes to my mind is Tarsila’s famous quote “I want to be the painter of my country.”¹ Tarsila do Amaral is a key figure in Brazilian art history and, in fact, if you were to randomly ask Brazilians on the street to name a national artist, they would very likely recall Tarsila—such is the great esteem and popularity she achieved in her efforts to paint ‘Brazilianess.’ This recognition is most attributed to her role in the emergence of Brazilian Modernism in the 1920s, even though she continued a lifelong career combined with art criticism until 1973.

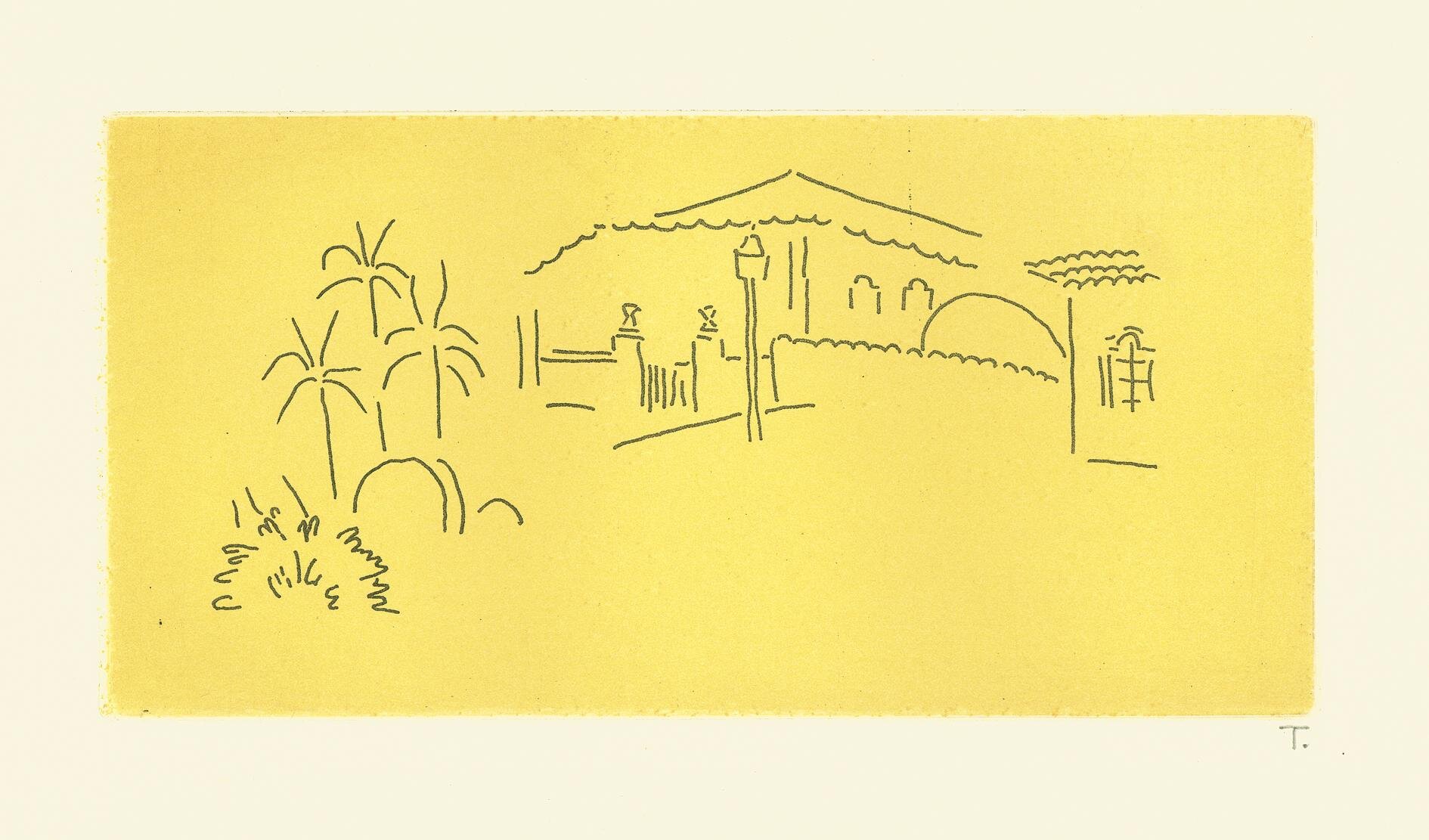

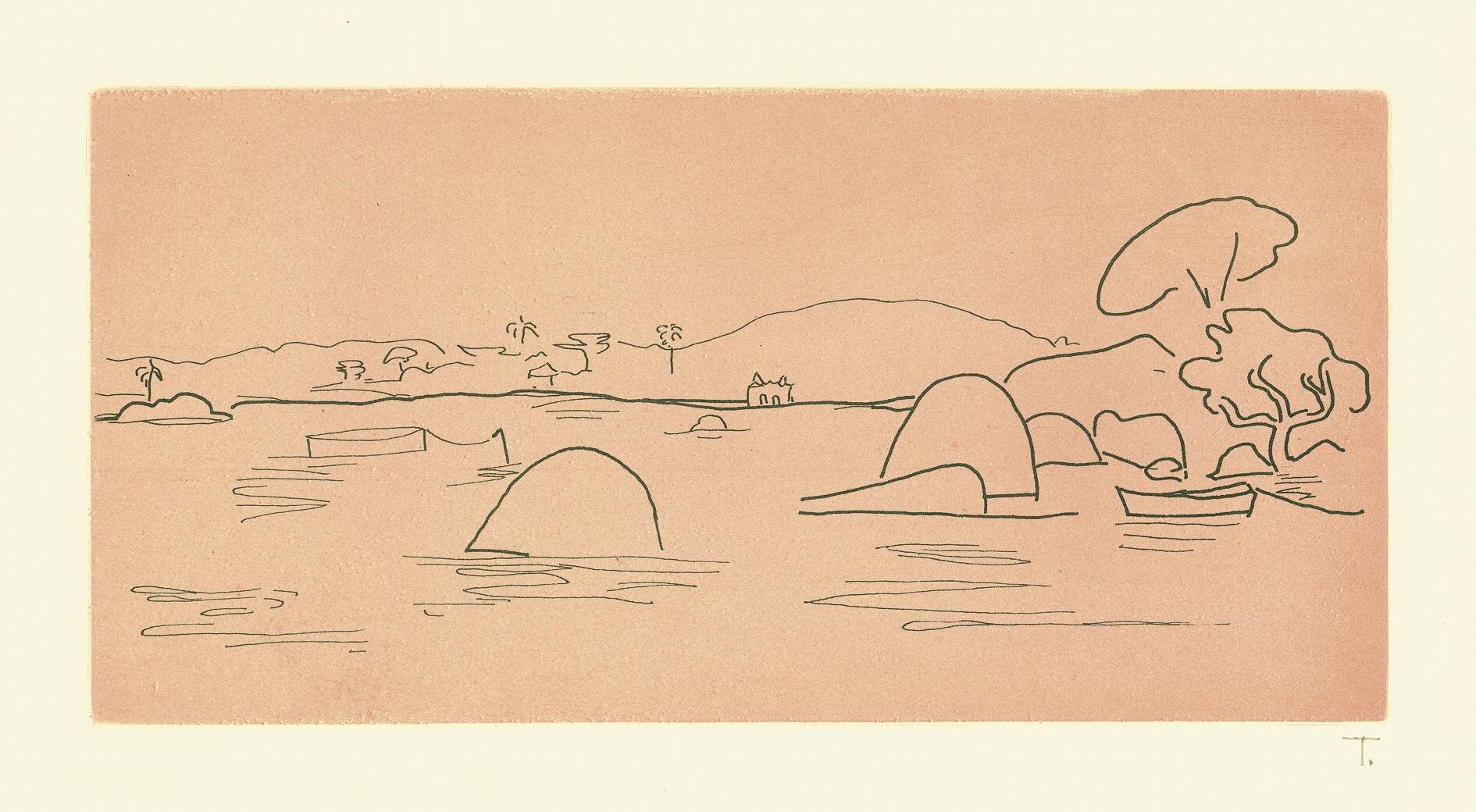

Tarsila came from a rural aristocratic environment that provided her with a privileged education as well as an idyllic infancy amidst the bucolic landscapes of São Paulo’s countryside. These were elements that would later deeply inform the development of her modern art and lifestyle. Joining a group of similarly upper-class, educated, young poets, writers, and painters in the city of São Paulo, she created highly-stylized images that exploited autochthonous aspects of the Brazilian rural landscape, as well as visual renderings of the modern city in line with a modernist project to fashion a new art and aesthetic against long-held European colonial models. Tarsila and fellow Brazilians took several sojourns to Paris where they participated in the bustling avant-garde cosmopolitan scene and incorporated new artistic ideas and techniques under the distant perspective of their native country. Tarsila was able therefore to craft a signature artistic style and build her career on both sides of the Atlantic. In the U.S., her work has been featured in several group exhibitions (the first in 1930 in the Roerich Museum in New York) and most recently in an overdue 2018 solo show at MoMA. While museums and scholars work to decolonize eurocentric narratives of modernism, Tarsila surfaces as an influential figure that connects transnational artistic centers, specifically São Paulo and Paris. Mexico City is another modernist hub in the first half of the 20th century that has been reframed using this perspective. Dali, could you explain how Frida Kahlo became known as such a major figure of Mexican art?

Dali: Well, I noticed in my study of these two women and particularly the commercialized re-imagining of their legacies, their backgrounds are often glossed over—even omitted. For example, one of Frida Kahlo’s most enduring artistic contributions is introducing the culture and history of the Tehuana women of the isthmus of Oaxaca into popular “media” consciousness. However, Frida wasn’t born in Oaxaca nor did she even spend a considerable amount of her life there. Yet, in the nationalistic renderings of her image, she is seen as a figure of “the people” and a continuation of the “indigenismo” of Mexico. I think that many Mexicans would agree that within the national identity, the state of Oaxaca is considered the cultural core. From the popularized Día de Los Muertos, to many of the national foods, to the enduring legacy of president and national hero Benito Juarez, Oaxaca is a state of incredible importance to Mexican state mythology. It makes sense, therefore, that Frida felt an affinity to the people as she was beginning her trajectory as an artistic and political influence in Mexico, even though her familial background reflects a very different history.

That is why your term “rural aristocratic environment” piqued my interest because I think that this describes Frida’s life quite well. Her father, William (Guillermo) Kahl, was a German immigrant whose life in Pforzheim, Germany, was one of education, comfort, and privilege. In fact, a wave of German immigrants had already colonized the Yucatán prior to William’s arrival. German immigrants to Mexico were welcomed due to their perception of being skillful farmers and astute businesspeople. These immigrants were granted access to opportunities in Mexico that were not offered to its indigenous or mestizo natives or the Mexican descendants of slaves. William Kahl was a part of a lineage of individuals incentivized to settle Mexico in order to develop it into an industrialized and modernized society under the helm of dictator Porfirio Díaz at the expense of rural workers who were robbed of their ability to own land without a formal legal title. In short, Díaz’s regime bequeathed land to corporate elites, investors, and foreigners while subjecting the Mexican people to starvation.

Although Frida couldn’t deny her father’s European ancestry, one of Frida’s classic fibs was that Guillermo was of Jewish-Hungarian ancestry when, in fact, he was born to Lutheran parents. This slight renovation to her life’s story, in addition to other famous lies that Frida frequently peddled around her origins and her proximity to Tehuana and Zapotec cultures, demonstrates how Frida had a hand in constructing a cultural ethos of her own that heavily relied on her self-exotification within Mexican society. As a member of the Mexican Communist Party (1927), Frida was staunchly against the growing influence of the Third Reich and German ethno-antagonism in Europe. Her association with Judaism, much like her association with being born in 1910, the culminating year of the Mexican revolution, helped establish her positionality to the themes that peppered her work: namely, marginalization, cultural amalgamations, and nationalism.

Fernanda, could you speak about Tarsila’s unique opportunities that her background afforded her?

Fernanda: Absolutely! I couldn’t agree more that within a larger narrative of these artists, there exists a flattening of historical and personal circumstances that inevitably come with the commodification of their artistic legacies, especially in Frida Kahlo’s case. Tarsila do Amaral has not yet undergone that global level of commercialization and, unlike Frida, who took her mixed-raced heritage as an impassioned subject in her art, Tarsila didn’t bother to focus on her white family’s lineage. Indeed, despite using slight countryfied traces in special occasions to differentiate herself as an exotic woman, Tarsila did it under the signature of famous Parisian fashion designers.² She was successful in crafting her persona as an adventurous, cosmopolitan, and refined white woman—an image that her family state has perpetuated all while curating expensive merchandise directed to high-class audiences.

Tarsila was born in 1886, just two years before the formal abolition of slavery in Brazil, the last country to do so in the Americas. This is notable because Amaral grew up in a period of transitional capitalism that included a remodeling of exploited racialized labor, which is visible in the microcosmos of her family's extensive coffee plantations. Many of the formerly enslaved people and their upbringing continued to work under renovated subaltern conditions for coffee barons like Tarsila’s father (who owned twenty-two estates alone in São Paulo’s inland). Young Tarsila and her six siblings then were taken care of by these people, sharing daily their Afro-American culture full of different customs, stories, and legends that she would recall as an adult as a source of inspiration for her work. Concurrently, the growing fortune resulting from the arduous work in the coffee plantations was converted into external investments. Coffee barons were open to invest in the modernization and new ideas shared with liberal professionals of the growing cities.³ Another aspect of this modernizing drive was to provide their children with a rigorous francophone and humanistic education. In addition to being educated in French language, French poetry, and classical piano at her family's rural home, Tarsila attended elitist catholic schools in the city of São Paulo. As a teenager, she spent two years with her sister in a boarding school in Barcelona, where she is said to have discovered her art passion while copying religious figures. In sum, from inside this rural aristocratic environment full of material privileges, Tarsila do Amaral inherited the symbolic capital built from tradition allied with a progressive attitude toward modernization, which she fully took advantage of to further cultivate her talents and come up with a groundbreaking artistic intervention.

Dali: I love that you began to lead us into an investigation of Tarsila’s educational pedigree, because we witness that both women had their formative years molded by European traditions, and Frida’s education definitely opened doors to an artistic and social development that was unconventional at the time. Prior to being accepted as a teenager into the most prestigious school in Mexico City, Escuela Nacional Preparatoria in 1922, Frida was educated at Colegio Alemán, a German elementary school, per the request of her German father. At both institutions, Frida had access to Mexico City’s European-adjacent elite. At Escuela Nacional, Frida joined a group of rambunctious Marxist-Leninist teenaged artists who called themselves ‘Los Cachuchas,’ much like Tarsila do Amaral’s ‘Grupo dos Cinco.’ The group's nine members included essayist Alejandro Gómez Arias, poet Miguel Lira, author Octavio Bustamante, and composer Ángel Salas. Admittedly, ‘Los Cachuchas’ dedicated themselves to socialist and communist theories that were motivated by the economic liberatory struggles of the Mexican people, however, the group at its core were wealthy “white” teenagers. Is this something similar that you noticed within Amaral’s young artistic cohort?

Fernanda: Yes. If we can establish a similarity between the Mexican ‘Los Cachuchas’ and the Brazilian ‘Grupo dos Cinco,’ it would be their eurocentric education and privileged conditions. Which, I think, would apply to many avant-garde movements across Latin America in the 1920s. What is interesting to me is to see how they used those tools to negotiate their subversive artistic projects while their identities evolved through other life experiences. And, as a result, what were the cultural and sociopolitical effects of those interventions? In this sense, Tarsila do Amaral and her comrades—the painter Anita Malfatti, the poets and writers Mário de Andrade, Menotti Del Picchia and Oswald de Andrade—were already in their thirties when they met, thus, I imagine they had more opportunities to execute their ideas than the teenaged ‘Los Cachuchas.’ I mean, both groups matured their intellectual thinking in informal meetings much like an enthusiastic brotherhood, but the ‘Grupo dos Cinco’s’ expansive networks allowed them to carry out their ideas in an event like the “Semana de Arte Moderna,”⁴ and publish their own magazine, Klaxon (1923). ‘Los Cachuchas,’ on the other hand, would keep their artistic experimentations confined to their adolescent circle, right? The influence of their haphazard fraternity would come out individually during adulthood, as casually reminiscent allusions.

What would come out even later in life for ‘Grupo dos Cinco’ members, in contrast, was their political awareness and, in Tarsila’s case, a brief Communist Party affiliation after her tour of the Soviet Union in 1931. In hindsight, Mário de Andrade himself criticized the naivete of the Semana de Arte Moderna participants (extended to all activities of Grupo dos Cinco) toward the stark social reality and popular struggles of their time. In a conference that celebrated twenty years of the Semana de Arte Moderna in 1942, he also pointed out that the financial support to the event and the embracing of Grupo dos Cinco's modernist cause by the São Paulo decadent aristocracy was not just a benevolent act. São Paulo’s monied patrons could afford the risk of investing in radical movements and subversive values because they themselves had established generational artistic criteria and they would become the eventual gatekeepers of that criteria.

Dali: Fernanda, you bring out such salient points about how radical movements are often co-opted or even promoted by elite classes because, often, these people have the least to lose. It reminds me of the United States hippie movement, which was really a countercultural movement that rode on the coattails of the Civil Rights movements of African-Americans, Mexican-Americans, Asian-Americans, and anti-war resisters. When historians look back on the participants who self-identified as ‘hippies,' however, we witness that it was a counterculture of middle class children. It was a common refrain among conservative politicians and pundits to call hippies “spoiled freaks'' as a way to discredit them and distill the Civil Rights movements that they were associated with. However, there is credence to that label if given a bit more nuance. The hippies were the spawn of means, of a bloated American society that valued materialism, domesticity, and the corporatization of labor. And American society was only able to do this because of the economic boom of WWII. Take, for example, the seminal musical figures of the hippie movement. Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, and Frank Zappa were all children of affluent, high-ranking members of the U.S. military. We don’t want to underestimate their impact and influence, but as you’ve already pointed out, these individuals had the resources to hone their crafts, the capital to purchase resources, and the psychological fortitude to “eschew” norms, all while their parent’s pensions, inheritances, and property awaited their return.

In her book Daughters of Aquarius, author Gretchen Lemke-Santagelo mentions “hundreds of women, mostly white, had transformed themselves into transmitters of native wisdom [...] unsurprisingly, this upset many Native Americans who rejected the piecemeal appropriation of their sacred sites, objects, and ceremonies and […] the removal of indigenous wisdom from its cultural and historical context.” Another aspect that we cannot overlook is how white and culturally appropriative the hippie movement was. Donned in East Asian prints, Native American regalia, and doused in South Asian incense, 1960s counterculture was “surprisingly” homogenous, part in parcel like the sociopolitical and artistic movements that came before them, including the movements that Amaral and Kahlo belonged to.

Fernanda: This is an unusual and very insightful comparison, Dali! Regarding cultural appropriation framed by the exoticizing gaze toward “the other,” I also recall the take on so-called “primitive art” by European avant-garde movements in the context of World War I. Half a century before the hippies, as you suggested, cubists, expressionists, and surrealists sought, in non-European cultures, namely African, Asian, and Native American cultures, an alternative not only for their stagnant artistic models but also for their increasingly industrialized societies scarred by the traumas of war. What is often forgotten behind such inventive modernist artwork resulting from those cultural encounters is, again, a decontextualization of objects and values taken from their original contexts and meanings by violent colonial incursions—paradoxically, the highest expression of what the vanguardists were protesting against.

As for the Latin American artists that flocked to European artistic centers at the time, their response to the desirous European expectations for primitivism could be as much a way to get into a competitive art community as a reduction of eurocentric stereotypes of Native Latin America. This particular detail complicates our understanding of Tarsila do Amaral’s artwork and her double-edged appropriative attitudes. While in Paris, Tarsila toyed with those primitivist expectations by working with the renowned cubist painters Albert Gleizes, André Lhote, and Fernand Léger, until carefully preparing her 1926 solo show (and a second one in 1928) at the prestigious Galerie Percier. By presenting a body of work composed of modern stylized renderings of black bodies, tropical landscapes and religious piety, while also showcasing a bourgeois self-portrait and several images of São Paulo’s modernization, Tarsila assumed but also subverted the European ‘othering gaze’ toward her art. It was an anti-colonial gesture—which I agree with the scholar Michele Greet—denotes a Brazilian “hybrid culture” strategically highlighted by Tarsila as simultaneously modern and ethnically different.

When the perspective is displaced to Brazil, however, the othering gaze departs from Tarsila toward her Indigenous and Afro-Brazilian counterparts. For instance, her 1924 modernist trip to colonial sites in the interior of Minas Gerais state and to Rio de Janeiro’s carnival in order to “rediscover the country” inspired the modernist sketches that Tarsila used for many of the paintings presented in the Parisian shows. This chapter preceded the apex of Tarsila and Oswald de Andrade’s creative partnership when they forged the idea of “anthropophagy” in 1928. Anthropophagy was a metaphorical allusion to the practice of pre-colonial Indigenous cultures of the Brazilian coast that ate their enemies to acquire their force and energy. To emulate it as an anti-colonial attitude, Brazilian modernists should devour European vanguardist techniques, nurturing from them to create a unique form of Brazilian art based on their native subjects and resources. Tarsila's renowned painting “Abaporu,'' which means “the man who eats” in the Tupi indigenous language, was the starting point to this ideology. As the scholar Edith Wolf noted, “Brazilian modernism emanated from a tripartite gaze that shifted frenetically from Europe to the Republican elite to a national Other and deftly navigated tropes of Brazilian difference through parody and adaptation.”

Thus, cultural appropriation was explicitly at the heart of the creative potential of all these Western 20th century artistic expressions we are trying to shed light on. But while European vanguardists and North American hippies were part of a culture and national identity they felt excluded, Tarsila and Brazilian Modernists—and you can tell me if this is the case with Frida and her Mexican fellow artists—were researching their country's diverse cultures to develop a national art away from external colonial powers.

Dali: You bring out salient details because in the 20th century nationalistic programming and repatriation of Mexico, its elite artists were all recruited to depict a unique and vibrant “mestizo” culture that “honored” Aztec, Mayan, and other indigenous groups like the Zapotec. Mind you, neither Frida nor her husband Diego Rivera had direct ties to the people of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and none of their biographies mention either artist spending considerable time in Oaxaca. However, as ambassadors of a new nationalistic identity predicated on “indigenismo” developed as a sociopolitical foil to growing U.S. American Gringolandia influence, both Frida and Diego had to advertise their “Latinidad.”

Consequently, Frida’s simplistic and modern style began to include the shawls (rebozo), skirts (raponas and enagua de holán), and tunics (huipiles) of the Tehuana women and other indigenous groups. Using modern metrics, Frida’s stylistic choices would definitely be considered cultural appropriation. But, I believe that even at that time, Frida was conscious that her artistic choices were not reflective of her actual lived experiences, despite any intent toward political solidarity. I believe that a view of her inner psyche is well represented in her piece, “Mi Nana y Yo” (My Nurse and I).In the painting, Frida paints herself with the face of a grown woman and the body of a child while suckling the breast of her much darker indigenous wet nurse whose face is covered in a “pre-Columbian funerary mask.” The wet nurse isn’t cradling the hybrid woman-child Frida and there is a palpable distance and lack of intimacy. Her wet nurse's right breast leaks milk, while her left breast is nutrifying Frida with an elixir as milk falls from a greyed and pregnant sky. It appears as if the wet nurse is offering Frida as a sacrificial offering, and although many scholars view this as a transformed rendering of “Madonna and Child” that illustrates Frida’s own separation between herself and her mother, I see it as a hint into Frida’s awareness of her “suckling” from indigenous identities to nourish her own. This could be said of Mexican society as a whole, especially during the time of Frida’s artistic maturation. Indigenous land and indigenous lives were merely a disingenuous access point for the modernization of Mexico—a faux-subaltern movement being led by the parties responsible for mass subjugation.

Fernanda: Definitely. The utilization of indigenous cultural pasts to boost a project of cultural emancipation from Western colonial domination toward a modern art was at the center of Mexican and Brazilian modernisms. But in Brazil, unlike in Mexico, a nationalist project took shape at the government level only after the 1930s Getúlio Vargas' dictatorship. Vargas' nationalist platform relied heavily on instruments of propaganda and censorship to foster a sense of unity in a country of continental dimensions. The promotion of samba (an original Black rhythm) to spread messages of political content, the transformation of “Our Lady of Aparecida” to a mestizo saint and religious patroness of Brazil, the decriminalization of capoeira and candomblé (sport and religion of Afro-Brazilian origins, respectively) were all sudden incorporations, part of a Brazilian uniqueness. Indigenous cultures also started to be approached through the scientific lens of anthropologists, particularly with the foundation of social sciences departments in the new University of São Paulo (USP). Social studies such as “Casa Grande e Senzala” by Gilberto Freyre (1933) followed the legacy of modernists in reevaluating the role of Portuguese, African, and Indigenous cultures in the constitution of the Brazilian “man,” shifting permanently the view of miscegenation as a positive Brazilian trait.

The rhetoric of a “racial democracy” that has permeated Brazilian popular imagination for so long took shape from such confluences sustained by a white supremacist mindset that promoted national identity through cultural appropriation but barely discussed citizenship in social and economic levels. In that utopian concept, each of the country's “founding” ethnicities had their own contribution in the composition of Brazilian culture and lived harmoniously with no racism. As the historian Marcelo Paixão mentioned, it works similarly as the “American way of life” or the French slogan “Liberté, égalité, fraternité,” and is called as much in civic celebrations as in the most infamous situations that require a “myth of origin” to arbitrarily explain the inexplicable—such it was the case of vice-president’s denial of racism in the brutal killing of João Alberto Freitas last year.

Dali: The “racial democracy” that you mentioned undergoes a different iteration in Mexico. During the nation's post-revolutionary era, Diego Rivera was famously enmeshed in tumultuous Mexican domestic contexts, also keeping ties with Russian, and U.S. American political scenes. In 1922, Rivera joined the Mexican Communist Party, and his subsequent muralist work centered heavily on working class struggles, agrarianism, and indigenous imagery. We have spoken about it at length, but Rivera was one of the “founding fathers” of modern “Mexicanidad,” i.e. “that special quality of being Mexican, one’s Mexican identity […] and the pride felt in being Mexican. It was an identity born of Mexico’s pre-Hispanic indigenous cultures and its colonial past, all mixed up with a post-revolutionary, modern, visionary future.”

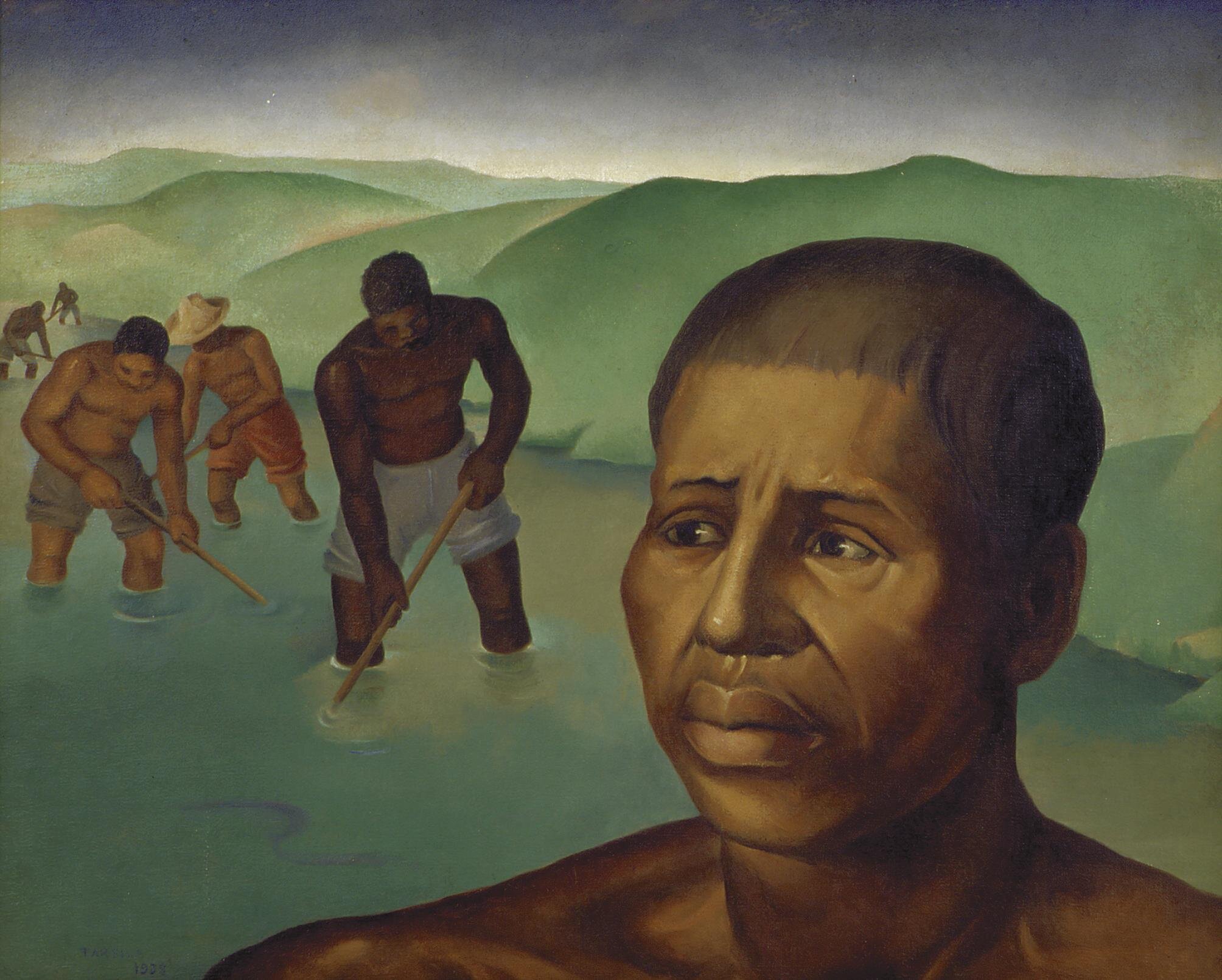

Fernanda: Right! During the 1930’s, Mexican muralism influence as well as social realist trends took hold over the continent and Tarsila turned to her “social phase” too. She made use of a more sober palette to paint socially committed artworks along with a new generation of artists. It was with her previous cheerful colors and celebratory body of work though that she began to exhibit her work in Brazil. The fact that Tarsila decided to not show the artwork “A Negra” (The Negress, 1923) in her first solo exhibition in Rio de Janeiro in 1929 also offers us a glimpse about how she navigated those sociopolitically convulsive times and more importantly, about the awareness that she had painted an almost caricatural image with painful stereotypical if not racist connotations. While she affirmed the painting was too ‘problematic’ to be shown in Brazil but did not explain why, in another commentary from her late years we can see her deep white elitist subjectivity:

“I remember one of the old female slaves […] that lived in our fazenda; she had droopy lips and enormous breasts because (I was later told) in those days black women used to tied rocks to their breasts in order to lengthen them, and then they would sling them back over their shoulders to breastfeed the children they were carrying in their backs. […] I stylize everything in my painting; what I saw or felt like a pretty sunset or this black woman, I stylize it.”

Although this testimony relied on nostalgic memories and it is evidently crossed with folkloric tales, it is undeniable that Tarsila’s stylizations in “A Negra'' were made at the expense of a dehumanized black body. The monumental figure occupies almost the entire space of the canvas, sitting in front of an abstract background with a banana leaf. We perceived it to be a woman just because of the large distorted single breast, which is the one Tarsila mentioned. Again, despite being understood as a contrast to the classical European white bathers, within Brazilian borders Tarsila radically renovated art history but failed to empathetically include a marginalized black individual in it. I would say that her economic position also precluded her from seeing a gender identification with “A Negra.” And this is another topic I would like us to address Dali: how these two women artists experienced their femininity and approached gender issues in their art, considering especially the position of Frida Kahlo as a woman with disabilities.

Dali: Sure, one aspect of Frida’s life that I have yet to highlight are her physical disabilities and the frequent and gruesome challenges she faced with her health. Frida’s physical health is what I would consider the most tragic part of her life and the most enduring visual contributions to her work. Many historians believe that Frida was most likely born with congenital spina bifida, but at the age of six years old, Frida also contracted polio, which affected the growth of her right leg and severely contorted her pelvic cavity. Then, on September 17, 1925 Kahlo was on a bus that collided with an oncoming electric car. Several of the bus passengers were killed in the collision, and the accident had left Frida critically injured with a handrail impaling her body through her pelvis and backbone. Frida’s road to recovery lasted for months and her sustained injuries would continue to cause her chronic pain for the rest of her life. Despite this tragedy, however, this particular injury was the seminal event that established her artistic development. The months she spent on her hospital bed and in bedrest were dedicated to sketching, reading, and painting. Frida’s father constructed a special easel that included a mirror that hung over Frida’s bed for her to experiment with self-portraiture and provided her with the tools and materials to create her art.

As tragic as this episode in Frida’s life is, her ability to not only receive the best medical care at the time but to simultaneously invest in her creative development is a testament to her socioeconomic status and resource availability. Fernanda, could you imagine what these injuries would have meant for a lower-class Mexican farmer or housemaid? The fact that this horrific accident didn’t decimate her future success or ability to earn an income must be emphasized because it would have been an uncommon accomplishment for the working-class individuals, particularly the Mestizx population, whose identities Frida's work was purported to represent. Much like Tarsila do Amaral’s cohort, the buoyancy of her social status allowed her to achieve prominence despite her physical disabilities.

Fernanda: With all honesty, Frida’s life story is astonishing in terms of her capacity for resilience. The fact that she made chronic pain the subject of her art can definitely be inspiring whenever people (facing similar situations or not) have the resources to reinvent their lives. The Mexican thinker Eli Bartra also argues that the elaboration of Frida personal feminine struggles in medium size canvases while her immediate male counterparts were painting monumental renderings of popular and collective themes constitutes the strong political side of Frida Kahlo. Not able to work in the murals because of her physical limitations, Frida’s autobiographical representations of pain, disability, androgyny, have been deemed as an anticipation to the 1960 second wave feminist slogan “The personal is political.” In both cases, there is a claim for the emancipation of invisible feminine subserviences (such as unhappiness, sex, house responsibilities, motherhood, childcare, domestic violence) through political intervention. As for Tarsila do Amaral, I noticed that like Frida, she had a starting point for her artistic career associated with a distressing personal episode. Tarsila gave birth to her only child at age of 20 while in an arranged marriage. In the years after her separation (the reasons of which were not clear, ranging from “differences in cultural levels” to cheating), Tarsila explored several artistic activities until she turned 30 and finally decided for a career in painting. She could afford a luxurious atelier in one of her family properties in the center of São Paulo and while investing in her professional life, motherhood appears to have run smoothly, too. Tarsila’s financial means allowed her to enroll her daughter Dulce in European boarding schools where she would visit often and took Dulce to vacations along with her partners and friends.

Whereas Frida Kahlo and Tarsila do Amaral were situated in different political geographies, they represent exceptional trajectories within a white elitist ethos in the first half of the twentieth century. As we noted, they had the support of their families to overcome early life challenges and build strong feminine subjectivities that were trailblazers in their respective modernizing chauvinistic societies. Still, even though both painters engaged with different approaches to social issues in their art and life, it did not correspond to an actually feminist experience. Neither were they interested in particularly advancing women's organizations at the time, nor did their socialist concerns contemplate women's collective struggles. Feminism—as I understand it today—requires empathy with other women's struggles and Frida and Tarsila individual success was in part constructed at the expense of it, even as an unconscious product of their time.

Could you tell me how you understand Frida's political evolution and relationship with Diego Rivera?

Dali: I view Frida’s trajectorial association with working-class ideologies as beginning with “Los Cachuchas,” maturing with her involvement with the Mexican Communist Party and the Young Communist League in 1927, and culminating with her relationship and marriage to Diego Rivera in 1929. At the time of her relationship with Rivera, he had also co-founded socialist-Marxist group of artists entitled The Revolutionary Union of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors. And like Kahlo, Rivera was a descendant of a family with ties to Spanish militarism and silver mining. In Rivera and Kahlo, we witness liberalism and socialist beliefs founded on the comfort of imperialistic exploitation and access.

An additional detail I found interesting in my study of Frida’s early life is the concurrent challenges with mental health that were very apparent in her youth. Due to the alienation she experienced as a child and the psychological toll of her chronic illnesses, young Frida developed moderate hypochondria that would eventually develop into Munchausen’s Syndrome. Frida would receive the inconsistent love of her mother and her family at her most ill, and consequently developed attention-seeking and distorted behaviors around affection. Those behaviors were incredibly evident in her relationship with Diego Rivera. A relationship which has been wholly distilled into a “complicated” love story where I see inappropriate sexual desires coalescing within an emotionally scarred and mentally unhealthy young girl.

Fernanda: It is interesting how you interpret such complex themes. We have been overwhelmed with so many retrofitted and commercialized messages about these artists that their concrete contributions (as well their flaws) are so difficult to grasp. I think that, as consumers of art daily exposed to all sorts of cultural influences, we have a responsibility to educate ourselves to avoid even more harm. If we don’t question cultural appropriative manifestations, as we saw they are tied with a history of discredit to racialized groups and aggravated by gender inequality, we are corroborating for the continuation of silencing and disenfranchisement of the non-hegemonic. I agree that no one “owns” a culture, but culture exchange requires a lot more effort to have reciprocal benefits and fair credit to all parties involved in it. As the line is often too thin, predictable capitalist mechanisms are always at play to neutralize any challenges to the status quo. Speaking of which, do you remember what we discussed on the dangers “decolonizing” art spaces face?

Dali: I do remember our conversations about racism within arts spaces, and I would like to bring your attention to Chaédria LaBouvier’s experience at the Guggenheim as the first black curator in the museum’s history. LaBouvier’s inclusion into the Guggenheim in 2019 was applauded and regarded as “a young woman who can look at this period in art history from a fresh perspective.” However, in 2020, LaBouvier denounced the Guggenheim's harmful treatment and “culture of law enforcement.” In a revelatory Twitter thread, LaBouvier revealed that the Guggenheim threatened to withhold her pay if she didn’t return a work badge and supplemental equipment—a retaliatory measure against LaBouvier because she refused to give up ownership of her curatorial work. Shortly after LaBouvier’s exposé, and on the heels of the Black Lives Matter protests, the museum released a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Action Plan. The summer of 2020 had many institutions scrambling to account for their racist histories.

However, the data⁶ inexorably shows that despite the performative messaging, Black people suffer higher rates of unemployment, thereby endangering their overall financial, mental, and health outcomes. You can see how cyclical and dizzying this issue gets and how easily these statements hide a larger problem that corporate bodies are unwilling to address because they are not financially incentivized to do so. The swiftness of the Black Lives Matter movement’s commodification should worry all of us because we are witnessing what happens when social, political, and commercial elites prey on radical ideas—the “othered subaltern” who need radical change the most are the very individuals who are cast aside. Appropriative history does love to repeat itself, doesn’t it?

Fernanda: Unfortunately! I am certain we could find other awful examples in the art world like what the curator Chaédria LaBouvier experienced because of a white colonial mindset that ‘invisibly’ has persisted in many institutions. Needless to say, it will continue to be a long battle against it and first-hand testimonies like LaBouvier’s open new opportunities to public discussion. On the other hand, I also acknowledge art projects that have succeeded in crossing oppression barriers and present more equity histories combined with fair work relations and multiple public involvement. In Brazil, I highlight the work of the artivist MundanoSP, who updated Tarsila’s artwork “Operários” (The Factory Workers, 1933) after joining townspeople affected by a ecological disaster to fight against the impunity of companies that continue to profit despite their legal and moral debts. Also, a book and art exhibition called “Enciclopédia Negra” (Black Encyclopedia) gathered contemporary artists and researchers of racially diverse backgrounds to account for 417 black individuals whose contributions to Brazilian history had been undermined until now. Examples can abound too. Just to finish my thoughts with a more hopeful perspective, which does not assure things are going to be done right, but at least indicates that with conscious choices, strong ethics and active listening we can better navigate the obstacles still posed by an obsolete white capitalist system.

I feel that I have already talked too much about a subject that we can continue talking about in an endless open conversation. Thank you for this meaningful exchange, Dali.

Dali: It has been amazing becoming your friend during such a chaotic time; thank you.

Footnotes

¹In Portuguese: “Eu quero ser a pintora da minha terra.” Letter from Tarsila to her parents sent on April 19, 1923, cited by Aracy do Amaral (2003, p. 101)

²Tarsila at the opening of her first solo exhibition in Paris (1926) wearing a Paul Poiret dress.

³For example, besides being a coffee baron—known as “Millionaire” due to his enormous possessions (which included once 400 slaves)—Tarsila’s paternal grandfather, José Estanislau do Amaral, was also an entrepreneur, having funded many hotels and a theater. In addition to this kind of construction, mansions, buildings, and new avenues transformed entire neighborhoods in the fast-growing multicultural São Paulo. Beyond these comforts of the modern city, railways and the introduction of automobiles facilitated the connection between the coffee plantations and their administration, which increasingly prompted the oligarchies to move to the city.

⁴The “Semana de Arte Moderna of 1922” (Week of Modern Art) was a three-day festival in the prominent São Paulo Municipal Theater that introduced the novelties in architecture, music, literature, and the visual arts anchored in an idea of rupturing with academic paradigms entrenched in colonial European models. Tarsila would clarify that she only felt compelled to innovate in her art when back in Brazil from her first stay in Paris months after the Semana. Her friend Malfatti had notified her by correspondence about the event and would later introduce her to its leading organizers— some of whom eventually comprised the ‘Grupo dos Cinco.’

⁵In Portuguese: “eu tenho reminiscências de […] uma daquelas antigas escravas […] que moravam lá na nossa fazenda, e ela tinha os lábios caídos e os seios enormes, porque, me contaram depois, naquele tempo as negras amarravam pedras nos seios para ficarem compridos e elas jogarem para trás e amamentarem a criança presa nas costas. […] Eu invento tudo na minha pintura. E o que eu vi ou senti, como um belo pôr-do-sol ou essa negra, eu estilizo.” Interview to Veja Magazine, 1972. Translation available in: https://www.rachel.com.br/2012/02/entrevista-tarsila-do-amaral-revista.html

⁶“…third- and fourth-quarter 2020 data finds slow and differing recovery paths across racial/ethnic groups. Hispanic unemployment remained 60% higher than white unemployment, while Black unemployment rose from 60% higher to 90% higher.” Source: https://www.epi.org/indicators/state-unemployment-race-ethnicity/

Dalí Adekunle holds a Master of Biomedical Sciences degree from Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine, and she is currently the Director of Community Partnerships at the Family Health Centers at NYU Langone Health. She was raised in a multilingual and multicultural household and speaks Spanish, Yoruba, Portuguese, and English fluently. Dalí is also a contributing science essayist for The Body. She loves to explore the descriptions of healthcare in popular media, and she has been published in Refinery29, Electric Literature, Wear Your Voice Magazine, CinéSpeak, Science For The People Magazine, and The Appalachian Mountain Club.

Fernanda Senger is a historian and has worked extensively in public and museum education. Born and raised in a southern Brazilian town situated on the border with Argentina, she obtained a B.A. in History from Pontifical Catholic University, which led her to study transnational cultural exchanges. In addition to Brazilian-Portuguese, Fernanda speaks Spanish and English fluently and has researched Latin American art and criticism as women studies inform it. She is now a Portuguese instructor and translator, and her artistic work has been featured in the Ridgewood Zine.