Los Santísimos Hermanos

Para leer esta historia en español, haz clic aquí.

“That is why, most holy brothers, here in this most holy little specter where we find ourselves, in this most holy little place, was where our most holy essence and most holy majesty of our most holy brothers, most holy nicolasitos, the leader of our group, or rather, of our most holy truth, ceased to exist…”

Thus opens Los Santísimos Hermanos, a short 8-minute documentary directed by Gabriela Samper and released in 1969. In the film, a male voiceover explains why he and his group cover the right half of their bodies with burlap.

“Because that’s the evil side where impurities will start to show from now on, in some way or another. And this side will be postimated, aphlegmated, cancered, hardened, paralized, according to the facts.”

Images of members of the group working in some rural area are interspersed with images of the same members with their burlap sacks holding up giant crosses made with two thin sticks, standing in front of tall buildings in a large city, Bogotá most likely. The voiceover continues: “The world is vice, it’s hatred, it’s vengeance, it’s politics, it’s pride, vanity, fantasy, greed, everything that belongs to the black slavery of communism, which is the same black ingratitude of the Amurecan Roman apostle. They are the same as what’s called Satan, the devil.”

This rejection of everything, the world, politics, religion, language, up to and including half of their own bodies, has fascinated me ever since. But my interest appeared to have come too late, since no matter how much I looked, I couldn’t find more sources besides Samper’s documentary.

I spent a few weeks trying to remember how I first learned about the Santísimos Hermanos (“Most Holy Brothers”), a group of Colombian campesinos who fled to the mountains to start a new life. Looking through my old conversations online, the oldest mention was on July 11th, 2014. That day, I asked my friend Julián Mayorga, a musician from Ibagué, to tell me more about the group.

Julián told me that sometimes his dad, who’s from Dolores, a town in the Department of Tolima (the capital of which is Ibagué), saw them walking around a few times, and that over there, they called them “encostalados” (“the burlap-sacked”). He also told me that he thought the founder of the group was from Líbano, another town in Tolima and one of countless places in Colombia whose name derives from the Bible.

Even so, the story was stuck in my head and what little I knew, I would tell to whoever was around to listen. I couldn’t believe that such an incredible story had been lost, that all the women and men who lived with that group deserved to have their story told. But I just didn’t know how.

Again, I was late. Just as the mystery of the Santísimos Hermanos started to unravel and satisfy my curiosity, the world at large shut down. Because of quarantine and travel restrictions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, several meetings, interviews, and stories had to be postponed and this story, for now, must remain unfinished.

Violence (Historiography)

Gabriela Samper is considered the first woman filmmaker in Colombia. Four years before her film about the Santísimos Hermanos, she had made another, El páramo de Cumanday, in which she brought some legends of the muleteers of Caldas (another Colombian departamento) to the big screen. They were the ones in charge of carrying and bringing goods by muleback through the steep mountains of central Colombia.

In 2004, her daughter Mady Samper told the newspaper El Tiempo that her mother died in 1974 due to the trauma of having been jailed and tortured by the Colombian government. She had been accused—without evidence—of being a guerilla member with the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (National Liberation Army), or ELN. That’s how she ended up as yet another statistic in a country shaped by violence. Violence that, at one time, seems to have shaped the Santísimos Hermanos.

For her documentary, Samper had help from Rebeca Puche Navarro and Hernando Sabogal. At the time, Puche Navarro was a psychology student at the Universidad Nacional in Bogotá. And in 1971, she published her thesis Los Santísimos Hermanos: A Study on Their System of Representation, which was based on observation of a “family” that was once part of the group. In the book, Puche Navarro analyzes the beliefs, behaviors, and even the language of a group situated in rural Nilo, a town in the Department of Cundinamarca, very close to Tolima. But the key part to understanding how this group found its way there can be found in the prologue, written by the thesis advisor, César Constaín Mosquera.

Constaín explains that “‘Los Santísimos Hermanos’ were a product of widespread violence, at a time when almost every traditional government institution was in crisis. Historically, we know that under these conditions, only protest or armed struggle could emerge.”

Before moving on, I should explain which particular violence, among the many we have in Colombia, I’m referring to. This was a period in Colombian history known simply as “La Violencia,” with a capital V. During this period, the main political parties in Colombia, the Conservative Party and the Liberal Party, were involved in an unofficial civil war that dominated daily living for a significant portion of the country.

It’s difficult to give exact dates for this period, but the majority of Colombians remember one date in particular. On April 9th, 1948, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, a Liberal Party leader and incredibly popular presidential candidate, was assassinated in Bogotá, resulting in a day of violence and destruction known as “El Bogotazo” that would only exacerbate the conflict.

In his book, Forgotten Peace, historian Robert Karl argues that there was an initial Violence that lasted from that date and until 1954, when representatives from both sides signed an amnesty deal with the dictatorial government of Gustavo Rojas Pinilla. Then, there was a second wave from that point until the 1960s, when several demobilized military units decided to take up arms again in the mountains and pass the war on to their children.

And so the killing didn’t slow with the amnesty deal. In 1962, the book La violencia en Colombia (“Violence in Colombia”), written by Monsignor Germán Guzmán Campos, sociologist Orlando Fals Borda and legal scholar Eduardo Umaña Luna, calculated that 200,000 Colombians were assassinated between 1946 and the date of its publication. For the most part, the killings were carried out by illegal militias and covered up by local authorities, who sought to liberate municipalities and departments of members of the opposition party in order to control elections, and in doing so, consolidate local power and land holdings.

In fact, Javier Giraldo, Alfredo Molano, and other authors in charge of the report Contribución al entendimiento del conflicto armado en Colombia, (A Contribution to the Understanding of the Armed Conflict in Colombia), which was organized by the Historic Commission on the Armed Conflict and Its Victims in Colombia (presented in 2015 during the Colombian government’s peace process with the FARC guerrilla), argue that “the main catalyst for the armed conflicts that took place in the country throughout the 20th century and into the present have been the recurring struggles for access to land.”

Beyond this, there were few ideological differences that separated both parties. So much so that Colonel Aureliano Buendía, from A Hundred Years of Solitude, the novel by Gabriel García Márquez, tells a recurring joke about the different civil wars fought in Colombia between both parties: “the only actual difference between Liberals and Conservatives is that Liberals go to mass at five o’clock and Conservatives go to mass at eight.”

But during the period of “La Violencia,” one thing united them with certainty: the conviction that bloodshed was a valid method to keep their rival from obtaining power. To that end, the Conservatives armed “Los Pájaros” (“The Birds”), a rural militia, and “Los Chulavitas,” a sort of informal secret police. For their part, the Liberals responded by supporting various guerilla groups.

In a new attempt to slow down this violence, the National Front was created in 1957. This was a pact between both parties to rotate the presidency every four years for the next three administrations (eventually extended to a fourth). As part of the agreement that created this governmental system, amnesty was granted to those who had been part of violent partisan groups. However, this did not stop the violence. Several members of these disbanded groups, both Liberal and Conservative, reorganized themselves and became bandits that, ideology aside, devoted themselves to robbery.

On February 11, 1960, in Gaitania, in the south of Tolima, Jacobo Prías Alape, a former communist leader who during his time as a Liberal guerilla member had been known as “Charro Negro” and later called himself “Fermín Charry Rincón” was killed by bandits. Four years later, his friend and protégé Pedro Iván Marín Marín, also known as “Manuel Marulanda Vélez” or “Tirofijo,” would lead the founding, in the same place, of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC by its Spanish acronym). FARC would dominate the imaginary of violence in Colombia for decades.

It’s in the midst of this violent context concentrated in the south of Tolima, very close to Nilo, that Constaín, Puche Navarro’s thesis director, believes we find the origin of the Santísimos Hermanos:

“Violence arises, among other things, when circumstances have reached a critical point, something akin to mental illness; it arises as the only solution allowing for survival. In pathology, we know that the psychotic break occurs when the patient’s world has become intolerable, when for reasons predominantly internal, but not just internal, their interpersonal relationships become untenable. Both for a healthy person, in which external causes are more prevalent, and for the future patient, in which internal ones are more prevalent, there are only three options: to die, to modify the environment in a radical way (which is on the other hand surely what the healthy person tries to do) or to go crazy.”

According to this psychological analysis, it was post-traumatic stress that cemented the aforementioned particularities of this group, it’s why “once cornered, without an exit, the Santísimos Hermanos were driven to search for a magical escape, to create a world of their own, with a specific way of life, illogical, unreal; in other words, they went insane...when confronted with truly unchecked violence. We see in the same place, the armed protest by Charro Negro and the crazed protest by the Santísimos Hermanos, who created a pacifist sect where, in order to continue surviving, they had to return to the neolithic era, mutilate the right side of their body, forego sexual relationships, limit their nutrition to a very poor diet, reject all technical elements that could make subsistence easier, remove themselves from communication with anyone with whom they might have something in common, and finally, eliminate anything positive and negative from their surroundings…”

Mutilation (Anthropology)

In her book, Puche Navarro describes the communal life of five members of the Santísimos Hermanos who lived then in Santa Bárbara, a rural and remote area of Nilo. These are the same Santísimos Hermanos who appear in Samper’s documentary. As Constaín explains in their prologue, the documentarians contacted members of the group in Bogotá in 1968, when the group went to the nation’s capital to attend the visit of Pope Paul VI. The five members, before becoming Santísimos Hermanos, were Luis (father, 40 years old), Ricarda (mother, 45), Zacarías and Virgilio (the two sons, 14 and 10, respectively), and Marta (a daughter, age not specified).

Nevertheless, as Puche Navarro explains, in becoming a part of the community, these five individuals stopped thinking of themselves as members of a family and came to see themselves as equals in a new context. “The Santísimos Hermanos broke with the family as an institution, sharing a very specific kind of relationship between the five members (who once formed a family).”

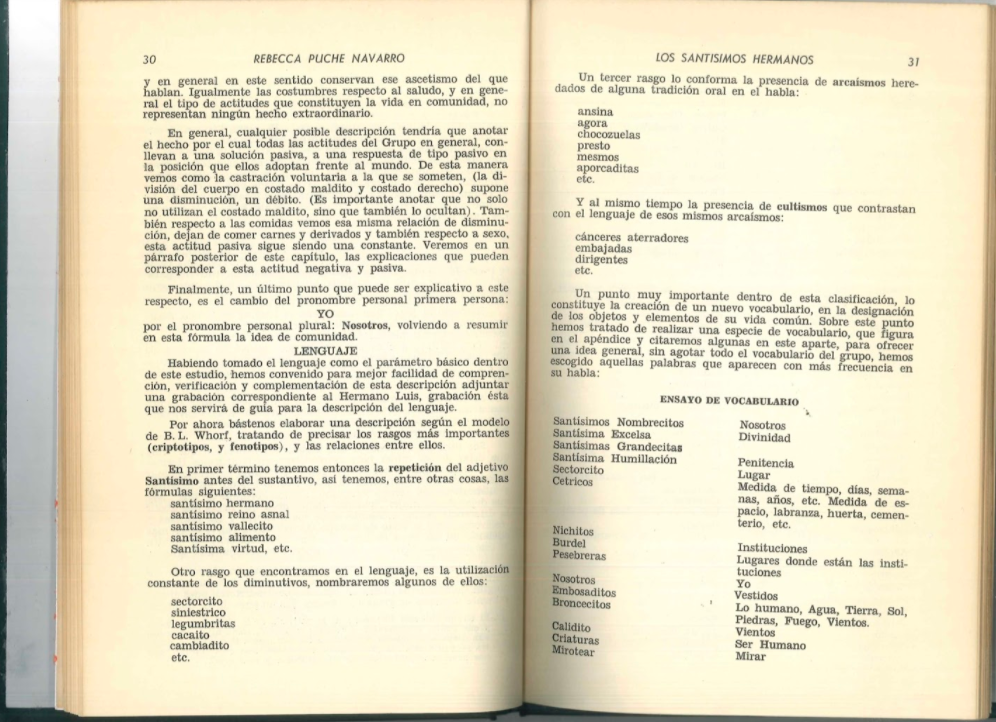

They didn’t call each other “mother” or “father,” they used “santísimos hermanos.” Also, as the thesis explains, “they also abolished sexual relations between members of the Group, calling it ‘Hijue pabajo pecao’ [something along the lines of ‘the goddamn downward sin’] and proposing “loving one another, loving everyone as the true siblings we are.” This is summarized in a kind of slogan that Puche Navarro reports as: “Todos semos iguales,” a mispronunciation of the Spanish phrase for “we are all the same.”

Although the previous lives of these five people are only briefly described, and we can’t know for sure if they were direct victims of The Violence, Puche Navarro agrees that this new lifestyle they chose derives from a massive trauma.

To explain this, he cites Maria Isaura Pereira de Quieróz, a Brazilian sociologist who summarizes it thusly: “Messianic movements coincide with moments of acute awareness, moments of crisis, which produce a rupture in stability and a change in social norms. The birth of messianic groups is therefore the response of a rural class abandoned to a given social situation.” She also uses Pereira de Quieroz’s idea to explain all the group’s deviations from the norm: “the range of activities carried out by messianic groups follow their own rhythm, a cyclical rhythm: creation myth–waiting for the messiah–development of the myth–the messenger’s arrival–evangelization–return to sedentary life–, etc.”

The legend starts with a man known as “Brother Nicolás,” about whom there isn’t much information in the thesis. Ten years before Puche Navarro’s encounter with this group of Santísimos Hermanos (which is to say, around 1961), Luis, the then-father of the family, was seriously ill (with which the author identifies as “possible asthma”). Upon learning of the reputation Nicolás had as a healer of sorts and as a miracle worker, they decided to leave Nilo and go visit him on Mount Pacandé, in Natagaima, a town in southern Tolima.

There, Nicolás cured Luis and taught the group the rules for living as Santisimos Hermanos. After living with Nicolás for a few months, and satisfied by Luis’ good health, the group decided to go back to Nilo and to continue living under the teachings of their new leader. In other words, they fully became Santisimos Hermanos.

A while later, the myth grew. Nicolás died near Nilo, probably in the middle of one of the long walks that, according to legend, he would make from Perú to Venezuela while preaching his beliefs and which had made him famous in various parts of Colombia. Thanks to those long walks, the group, around the time of Puche Navarro’s thesis, had about 80 members in places as far off as Santander, Valle de Cauca, the outskirts of Bogotá, and of course, in Tolima and Cundinamarca.

Luis and another santísimo hermano, Macario, looked for an anthill near the home of the group in Nilo and that’s where they buried him. The site became a place of penance for all members of the Santísimos Hermanos.

From there, they created rituals. Visiting Nicolás’ grave was known as the “most holy little humiliation” and consisted of walking, from any of the various parts of the country where members of the group were found, until reaching Nilo, where the sacred site was located. Once there, they stopped to read Nicolás’ manuscripts and, while they were at it, helped the members living there with housework.

But collaboration wasn’t just a trait the Santísimos Hermanos appreciated, it was the essence of their worldview. Forced to abandon society because of a war that divided people into mortal enemies, and having rejected a modern world that made such hell possible, the self-imposed restrictions of this same group made it so that each member couldn’t possibly survive without the help of the others.

These restrictions varied greatly. On the one hand, according to Puche Navarro, the Santísimos Hermanos “stopped eating anything that could come from the so-called ‘donkey kingdom,’ that is, the animal species. They rejected meat, fish, eggs, butter, cheese, milk, etc., only allowing themselves to eat vegetables, legumes, fruits, and grains. Their diet was macrobiotic.” Or, as we would now say, they were vegan.

“Likewise,” the author continues, “they completely reject everything that is mass produced, like chocolate, and prefer cacao, ‘cacao beans, because what comes from a factory comes skimmed, in turn, the beans still have all the flavor.’ The same with bread, coffee, corn, etc.”

Moreover, this food was obtained by growing it on their own land, or by “setting up ‘the most holy little embassies,’ which is when they go out in pairs, traveling throughout different regions while preaching and promoting their beliefs and doctrine. They don’t accept money or charity, only allowing themselves to accept food and necessary sustenance.”

Furthermore, “all the instruments they used are made of stone or wood, the latter being their preference, so that all the knives, spoons, and farming instruments, sowing tools, etc. were made of wood or calabash. This aversion toward metal objects seems to be the same rejection of technology. To justify it, they turned to a metaphor of returning: ‘we will return to the way things were’ and ‘the moment will come when the spirit will flourish.’ Following this same line of thinking, we find that they also reject the use of money, which they called ‘corneja’ [‘crow’] (a word with which they will use to name all objects resulting from progress and civilized society, such as electronics, radios, lamps, cars, fabrics, dresses, machines, etc.).”

Their wardrobe, or “Santísimo broncecito” (“most holy little bronze”), consisted of “different kinds of tunics made of plant fibers or yute [burlap], covering the entire body, while hiding the right side (which they call the left, left side and evil).” This style of dress, moreover, prevented them from using their right arm and hid their right leg, which they only used to walk.

Here is where we see the spirit of collaboration. Because of their vegan diet, they were forced to eat, according to Puche Navarro, six to eight times a day. In order to get food, they had to make use of rudimentary agriculture tools or rely on the kindness of strangers they encountered in their “Most Holy Embassies.” And on top of that, they could only do these things using one side of their bodies.

Under these restrictions, “collective work as a group is required of every member of the community,” and according to Puche Navarro, “they thought about recovering other parts of the body...That’s how we have it so the farm work is done for the most part individually, although the garment work could be done collectively with the help of every left side of each member of the Group (in other words, Brother Luis and his two sons), it’s as if after the voluntary mutilation required, they would start to see themselves as members of a community, of a Group, leaving behind the possibility of feeling isolated and becoming part of a Community.”

Baptism (Linguistics)

According to Puche Navarro, “one of the group’s most important customs...is the ‘Most Holy Baptism.’ At the heart of this baptism is the ‘Most Holy Temorcito’ [‘The Holiest Little Terror’] and the rejection of Christian baptism. In other words, the baptism through which you joined the Group and through which you acquired your true name, ‘the other is a nickname,’ was the result of the ‘Most Holy Temorcito,’ and not the Christian faith.

In this way, the (symbolic) mutilation described above wasn’t just corporal, but instead applied to all people, things, and ideas, and represented a radical break with the world, a reinterpretation of life, and everything that implied. A reappropriation and, at the same time, a rejection of the supposed truths the Catholic religion taught in a Catholic country. And the ultimate goal of this rupture was to destroy hierarchies and make all the members equal. This was clear in the religious rituals and in the particular dialect, or more precisely ecolect, that the group developed.

For example, the group rejected “sexual relations between members of the Group, calling it ‘hijue pabajo pecao’ [explained above] and proposing ‘loving one another, loving everyone as the true siblings we are,’ and in this way, converting the household into a Group of Siblings” (although Puche Navarro reported that members of a Bogotá group did have children).

On the other hand, one of the most important religious rituals consisted in recitations of “Song-Litany in unison...that ended with ‘tearing down the hijue pa’bajo pecao’ which are done ‘when you wake up, when you gorge [on food], when you finish doing that, and we go lie down to become delirious.’”

Initially, this “song-litany consisted in repeating the phrase “most holy ozanitas” (‘chants’), but afterwards, it grew to include “Most Holy Aperfumaditos [Perfumed people], Most Holy grandecitas [big things]’ etc.” This obsession with sanctifying everything you could name had a very clear objective: demystifying it, democratizing it, and elevating it, in order to be able to reclaim it. If everything was holy, nothing was really holy. Everything was on the same level. And just like that, everything was within reach.

Puche Navarro explains that “the truth (the most poetic of their ideas) consists in teaching and possessing the true name of things. They are named for what they are: in other words, as “Holy,” and that’s what makes them what they are. The “Holy” part is put in parenthesis, it takes them out of their false existence: the descriptor returns them to their true essence.

But this process was limited to the restrictive world they decided to create. The adjective Santísimo [“most holy”], the author explains, was “used when making reference to the nouns representing a specific sector of reality; the practical aspect of their beliefs. So we find that they use ‘most holy’ to designate their own, to refer to animals, to food, to the plots of land they cultivate, work, to the objects they use, and in general, to every element belonging to the rural countryside and around where they lived. (Which is to say, they used ‘most holy’ to describe farming, work, and the elements and customs of their world, without using it when referring to the elements and practices of their world, without using it when referring to elements that were foreign, as in the case of works of art, planes, because they didn’t belong to their immediate reality or simply had nothing to do with them).”

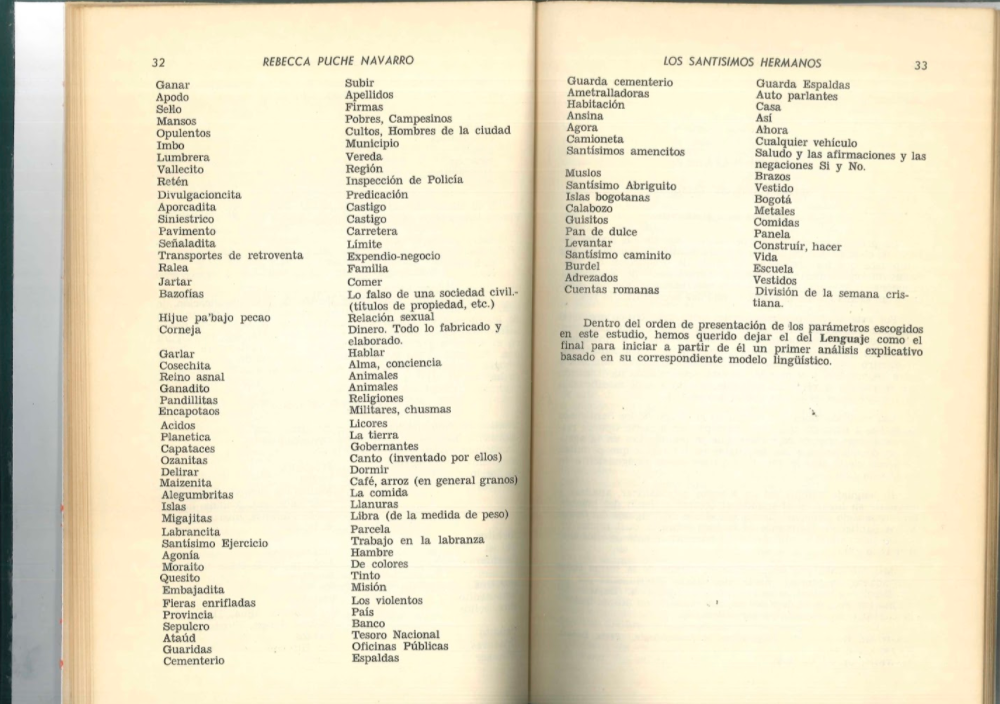

A short summary of this reality can be seen in the vocabulary found in the book:

Mount Pacandé (Semiotics)

The legend of Nicolás persisted. In 1995, an Ibagué resident named Walter Cataño, who is now a high school teacher, arrived in Mount Pacandé, in Natagaima. Back then, brother Lisandro was leading the group of Santísimos Hermanos that were living in the area where three decades earlier Nicolás had been a healer. Cataño has his own version of the legend.

According to him, Brother Nicolás showed up in the 1940s walking through various parts of Colombia, Venezuela, and Ecuador, without anyone really knowing where he had come from. The mystery was amplified by the fact that he didn’t carry papers or any kind of identification. In any case, people were drawn to him because of his visions, some of which were premonitions. One of the prophecies said that “time will shorten and the pound will weigh less,” in reference to how some foods, like potatoes (sold by the pound), would get more expensive.

In one of these visions, Brother Nicolás was told to go to Mount Pacandé and settle down. There, he started treating the sick and performing miracles. Cataño remembers a story in which Nicolas hit some rocks and water began to flow from them.

According to an article published in SoHo magazine by Marta Ruiz, who, by chance, came across Lisandro’s story in 2007 while researching Mount Pacandé, Nicolás was from Líbano (Tolima), and had settled in Natagaima in 1958 (although no sources are given for these dates).

That’s also where Nicolás came up with the burlap wardrobe that would become his group’s signature. His reasoning, according to Cataño’s knowledge, was that “a machete can’t penetrate such a cloak [made out of burlap or plant fibers]”. Those cloaks would cover the right side (or “lefty”) of the body, since that’s the “malignant side, seeing as how we use the right hand to grab weapons and hurt others.”

That reinforces Constaín and Puche Navarro’s hypothesis that what led to the creation of the group was the rejection of violence. Even more when the machete, specifically, was tied (at least in the national imaginary) to the horrors of partisan violence.

But Cataño also remembers another detail: the burlap sacks had a gourd (or container) stitched on the inside of the right side, which allowed the right hand to be placed inside in order to ensure that it wouldn’t be used. Even when they asked for donations, they didn’t use this pocket to carry food. They only brought with them that which fit in their left hands.

Ruiz’s article also mentions something neither Puche Navarro writes, nor Cataño remembers: that those who broke the rules were punished with whippings.

Although it’s unclear whether this punishment was real, the group's peculiarities made it so that, in general, people were suspicious of them, and according to what Cataño heard, people saw the “embassies” (or “missions”) as dangerous. Some Catholics in the area considered them demonic, and according to the stories told, some Santísimos Hermanos were stoned, burned alive, or lynched.

But Cataño joined the group when that was already lore. According to his own words, he was a “student dedicated to alcohol.” When his health was failing, someone recommended he visit the community for treatment. There, he met Brother Lisandro, who put him on a vegetarian diet and helped him get better. He also made Cataño rethink his life and realize that “spirituality was the path.” But a lot had changed by then.

During the mid-1990s, when Cataño joined the group for a little more than a year, “the customs were nothing like they were before.” Lisandro, who is from Planadas, another municipality in southern Tolima, had been leading the group for decades—since 1975, according to Ruiz’s article. But at some point (Cataño believes it was in 1990), he was invited to Bogotá to meet “an Indian guru.” Cataño doesn’t remember the name of this guru, but it was most likely Sant Ajaib Singh (also known as “Sant Ji”), who visited Colombia on several occasions until his death in 1995. This guru taught Lisandro how to meditate and to practice Surat Shabd yoga.

For about four years, Lisandro was alone in practicing these new activities. But afterwards, before Cataño’s arrival, he shared them with the entire group. Everyone would have to get up at 3 AM to meditate and everyone would learn to practice yoga. They all continued being vegetarian, but they only had to practice abstinence and restraint in Mount Pacandé. Also, their wardrobe changed: the burlap sacks now didn’t cover half the body but rather they wore something like overcoats with two long sleeves, a skirt, and a hood. With that, the majority of restrictions were lifted.

This was the group, some ten or so people, that Cataño knew and that are shown in some photos and interviews in the documentary Los encostalados del cerro (“The Burlap Sack-Wearers from the Mountain”) produced by Señal Colombia in 2012. In that same documentary, Brother Lisandro appears on camera in traditional Western clothing: a white shirt underneath a plaid shirt and a cap. Why?

This change, according to Cataño, was the result of others making fun of the burlap sacks. The Santísimos Hermanos had become well-known throughout the region as an eccentric oddity from Natagaima. They were already known as the “encostalados from Natagaima” [Natagaima’s burlap sack-wearers”]. So much so that, in the documentary, Lisandro shows a stamp that the municipality of Natagaima had put out with a photo of them wearing their burlap sacks. But at some point, near the start of the 2000s, things got out of hand.

Each year in June, Ibagué celebrates its patron saint festival. Part of the celebration includes a day in which several municipalities in Tolima send a delegation that marches through the streets of the regional capital in traditional attire. On one occasion (in 2003, according to Cataño), the Natagaima delegation marched while dressed in burlap sacks. This celebration tends to include large quantities of alcohol, which really annoyed Lisandro, who decided not to use the burlap sacks anymore and to burn them all, except one, according to what Cataño told me.

In the documentary, Cataño visits the house atop the mountain, where there lives Brother Álvaro lives alone, and who Ruiz describes in her article as “a 40-year-old former gang member from Ibagué, who had started reading about esotericism and gnosis when they were young.” In the documentary, Álvaro is the designated keeper of the history and traditions of the Santísimos Hermanos (and of the house, where you still see portraits of guru Sant Ji).

Álvaro tells Cataño, his son Santiago, and his student Dania Barrios, that Lisandro ordered him to save only his “robe” (which he shows), the one he wore as he traveled throughout Colombia on foot. In Ruiz’s article (from 2007 as previously mentioned), Lisandro is cited as saying: “four years ago, we stopped wearing burlap,” which confirms the date that Cataño had given. “We paid a penance of 30 years wearing the burlap sacks, but afterwards, people made fun of them, so we dropped them.” But Ruiz offers an alternative theory (also without proof): “four years ago, when they were still wearing the burlap sacks, Vidal, the oldest member of the community, burned to death. Apparently, a spark set the cord on fire and, in a matter of seconds, he became a human pyre.”

Velú Crossing (Dialectics)

But who am I to decide what is fact and what is fiction when it comes to this group? I haven’t been there to speak with them, with half of my body covered in burlap, meditating before dawn. All I have is a book, a film, and a handful of interviews to try to better understand this story.

In this same film, Álvaro summarizes the four processes that the Santísimos Hermanos have gone through: the first, which includes burlap wrapped around half of their bodies; the second, in which the number of followers increased “because there was less sacrifice required” (since they were then able to use both sides of their bodies); the third, in which they “joined those on the path;” and the fourth, which they were in during the filming of the documentary and which had them “preparing the land so people would come, since this place is going to be a refuge for a lot of humanity, because what was coming is going to be huge.”

The “path” references the (Catholic) processions that took place every Holy Week at the top of Mount Pacandé. At first, Lisandro, just like Nicolás, made the trip on his knees. Then, Lisandro and members of his group would sometimes join these new Catholic processions (on foot) in order to tell parishioners about their philosophy.

Regardless, according to Álvaro, Lisandro would assure the members of the group that at that point they would only reach “a certain level” and that they would be leaving, pulled away by love and other pursuits. That would leave an opening for the fourth process, which nobody knew better than Lisandro.

But I can only tell this story up until this point. According to what Cataño told me, Brother Lisandro doesn’t use technology. When I asked the disciple where I could find his old teacher, he told me to go to Natagaima and find the Velú Crossing on the road that leads to Neiva. They told me I wouldn’t have to give him a heads up. Lisandro would be waiting for me there and would know I was looking for him.

I was planning to test this theory on March 13th. I was going to go with a photographer friend to conduct more interviews and track down documents, photos, maybe even the stamps with the brothers wrapped in burlap sacks. I wanted to try to understand what being in the Santísimos Hermanos had meant for the members, as well as for the Natagaima community, Tolima, and perhaps for all of Colombia.

Anyway, the quarantine in Bogotá, where I live, began on the 19th of that month. I decided not to take the risk of traveling in the midst of such an uncertain time. And now I’m left with only the thought that brother Lisandro is waiting for me when this “really huge” thing that we’re going through is over.