The Submerged American West: An Interview with Kali Fajardo-Anstine

Para leer esta entrevista en español, haz clic aquí.

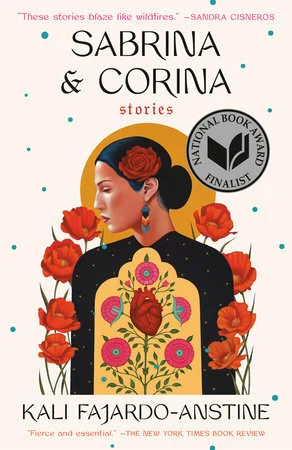

I don't remember exactly when and how I stumbled across Kali Fajardo-Anstine's debut short story collection, Sabrina & Corina, but I can no longer imagine my reading life without it. It is a collection that shocked me into myself, a collection in which I felt seen, and held.

Kali's creative project is centered in the mountainous expanse of the American West: specifically Denver, Colorado. Her work peoples the urban and natural landscapes she grew up in with the voices of those whose stories have been erased from their traditional homelands.

She unearths forgotten mythologies and matrilineages, giving searing, unforgettable voice to the indigenous women and girls who have made their homes and lives in Colorado for millenia. She guides us with a sure hand through their pleasures and pains, desires and heartaches and violences, and I am glad for her clarion voice in the constellation of Chicane/x literature.

Her next book, a novel, is historical fiction about a Latine/x woman, and will be published in English next year. Sabrina & Corina will be translated into Spanish soon, and I hope you read, and find yourself in both.

I know you have recently had an opportunity to partake in a residency at Yaddo, where you finished your next book project (¡felicidades!). Can you speak a little bit about the role of residencies in your writing life, and what it means to have that gift of time and space? How do you approach and segment the time you receive?

I began applying for residencies about a decade ago. The first residency that offered me a spot was Hedgebrook on Whidbey Island, which was such an enormous confidence and networking boost for me. At the time, I was in my early twenties and had only published one short story in a literary journal. The landscape was oceanic and rolling hills and unlike anything I had experienced growing up in Colorado. Inside my cottage was a journal where writers who had stayed there before me wrote their names and small messages. It was incredibly thrilling to see words from writers I deeply admire within those pages. It felt like I was a real writer, like I was being nurtured and supported by this web larger than myself. Residencies have helped me widen my writerly network, allowed me to experience different landscapes and American cultures, and have put me in conversation with literary figures whom I would never have met otherwise. I also am deeply drawn to the history of places like Yaddo and MacDowell.

I admire how honest you are on your social media accounts about the day-to-day grift of being a working writer. Can you speak a little bit about that hustle, and what it was like during the pandemic?

I recently watched the PBS American Masters documentary on Flannery O’Connor. From the archival footage, there was a moment when her editor, Robert Giroux, said rather bluntly with a comical tone, “Flannery made no money off her books. That's why she went out on speaking tours.” I had to laugh because the thought of Flannery O’Connor having to go out on speaking gigs to make a living hadn’t crossed my mind before.

During the pandemic, artists of all sorts suddenly lost their sole source of income—gigs. It was rough and terrifying. Many watched their entire calendar of upcoming jobs disappear, but of course this was happening in different industries all over the world.

You have recently participated as a judge in literary contests, and have written reviews of forthcoming books for various publications. Can you speak to the importance of engaging with emerging writers in this way, and the importance of having BIPOC “gatekeepers” uplift and review new work, helping to build upon the canon?

To begin, I’m not sure I agree with the idea of gatekeepers. I know we desire some measurement of what is and isn’t’ exceptional art, but the old systems of ushering only a select few through these narrow passages seems harmful in many ways, and of course intrinsically tied to advertising and capitalism, which is one side of writing—the industry side, the publishing side. That side, in my mind at least, is devastatingly separate from the art making itself.

I suppose, one of the main reasons I want to judge contests and write reviews and engage with new work is because this is my passion and I want to know what beautiful and strong and strange and unique work is being created. I want to uplift what catches my eye and attention, and I want to talk about books with others. I love literature—through and through.

So much of your work in your short story collection Sabrina & Corina is deeply rooted in place. Do you think you’ll ever run out of stories to tell in the Colorado and New Mexico area?

No, never.

Sabrina & Corina has been translated into a few languages recently: I feel like the stories in the collection are so deeply rooted in the American West, and am curious about what the translation process was like. Were you in touch with your translators? What are your thoughts on audiences who may not have a sense of the context and the places where the stories are set interacting with the world of the collection?

For much of my life, I felt underheard and invisible and to have my stories shared in not only English, but moved and labored over and presented in other languages has been such a moving experience. The first country outside of the U.S. where Sabrina & Corina appeared was Japan, translated by Yumiko Katoke, who also translates authors like Alice Munro and Jim Shepard. Yumiko did ask me some questions about particular words and images, but it was my intention to write universally understood stories filled with emotional resonance, stories that speak to our human condition and transcend place. Sabrina & Corina recently appeared in a Japanese rap video with the artist MoNa aka Sad Girl, and the book received a positive review in the Vatican newspaper in Italy. I’m doing an online event soon with my Italian translator, Federica Gavioli. It’s been such an honor to see my work travel the world.

You speak, and write about indigeneity, and your ancestral culture. Do you feel that your role as a writer is one of an archivist, unearthing voices that have been lost?

While I work with many exceptional archivists when I’m conducting research for my novels and stories and I once wanted to become an archivist myself, my primary role as a writer is a storyteller—to honor what interests my mind, to follow those instincts and musings. The stories I tell have never been hidden or lost within my family and community. In the critical examination of the short story The Lonely Voice by Frank O’Connor, he presents the idea of the "the submerged population group,” a term used to describe those who are pushed to the fringes of society. Colorado Chicanxs of blended ancestry of European and Indigenous (and in my case also Filipino) descent are definitely “a submerged population group” within the American West and the United States as a whole, but inside the homes of my own family, we are everything—we are the entire world. I am just telling stories the way I know how, and the way I want to.

I loved reading your thoughts on creating your own Yoknapatawpha County, a place of our own that holds lost history. Can you speak about the process of inventing the fictional town Saguarita and why you felt the need to create a town that didn’t exist to place your stories in?

When I first started writing the stories in Sabrina & Corina, and later chapters in my forthcoming novel, Woman of Light, I realized that I only specifically knew Denver, but many of my ancestors had only arrived there by the 1920s. At the time, some had come from the Philippines and others had arrived from Southern Colorado. I naturally started writing about a small Southwestern town, but it wasn’t exactly any place one could locate on a map. It was a fictional space that I had inherited through the stories of my elders. This space, I realized, needed to be fictional—it existed in another realm, another time period. It wasn’t our exact universe. And, perhaps like a true novelist, I enjoy the act of inventing. It’s pleasurable for me.

Can you speak to the connections between the short story form and oral storytelling? Do you come from a family of storytellers, and what drew you to the short story form for your first publication?

My first ideas for books came to me as novels. I wanted to be a novelist since I was a little girl, but once I entered the academic creative writing space, I was steered away from longer works. During my MFA years, novels were often considered too unwieldy for the classroom workshop.

As a former bookseller and teenage loner who consumed books like air, I have never separated storytelling forms—oral or otherwise. As a younger person, I was raised by a performer mother, a storyteller. I read and listened to storytelling modes that interested me. I wrote poems and small stories and chapters for novels. This wide ranging way to receive a story has also led me to work often deemed “experimental,” though I wouldn’t use that word myself. I recently read two books by writers whom I had been in residence with at Yaddo. The Book of Jon by the poet Eleni Sikelianos and Homesick by Jennifer Croft, Booker-winner Spanish, Ukrainian, and Polish translator. These books were formally astounding to me and while very different, both incorporated photos and nonlinear time. As a writer, inspiration comes to me in many forms, and through innumerable vehicles for communication and storytelling.

I know that you work with the team at One World, who publish incredible work by BIPOC authors. What does it feel like to hand over your first novel to your editor, and what has the editorial process with One World been like thus far? What has it been like as a non-white, non-New York-based writer breaking into the publishing industry?

Turning in Woman of Light is perhaps the single greatest accomplishment of my life thus far. I began thinking up this book as a teenager, and I wrote and rewrote for over a decade. I signed a two-book deal with One World just as the imprint was being born, this was back in 2017. It is my first and only experience in the publishing world. I’m happy, I feel listened to, my work is honored and protected.

I’ve seen you speak about your first novel being a work of historical fiction. Can you speak about what the research process was like, and how you stumbled upon the story? How did you handle the loss of history, and the blank spaces I assume you encountered in the archives while researching?

It was long and strange and filled with wondrous moments. This book began with my ancestors, the stories of my elders, their lives which seemed larger-than-life. My great-grandma and my Auntie Lucy talked incessantly about their lives coming north to Denver in the 1920s. They talked about my snake charming uncle, Lucy selling joints to flappers on Curtis Street, my butch auntie who protected and made it possible for all of them to move north, their lives in the beet fields, their Belgian coal miner father who abandoned the family. These women elders meticulously documented their lives, collecting household items–-irons, washboards, beaded dresses, ceremonial purses, small notes in cedar hope chests, grave markers.

I am not the first storyteller in my family. I am just one in a long line whose collective knowledge spans generations.

There have been some incredible books by BIPOC writers recently that expand our views of the American West. Can you speak to where you see your work fitting into the canon of great novels of the American West?

Here I defer to my readers, for this will ultimately be their decision.

The stories in Sabrina & Corina are often complex family stories, and I’m curious to hear how much of that work is inspired by your own family history. When writing, were there aspects of your family and community that you were inclined to conceal, or to spotlight?

Remember what Kiese Laymon once said: “You never tell all the secrets when you're trying to get free.”

Finally, I’d love to leave some space for you to share some recommendations for Chicanx and Latinx writers whose work you have admired recently! Who are you reading?

Something incredible happened while I was at Yaddo this past May—I was in residence with Angie Cruz who most recently published Dominicana, and the poet, translator and essayist Carina del Valle Schorske, both of whom are such gifted writers. I’ve also recently reviewed the wonderful and strange short story collection Eat the Mouth That Feeds You by Caribbean Fragoza. I love the poetry of Ada Limón, Eduardo Corral, José Olivarez. Xelena González is an incredible children’s book author from San Antonio (who also does a number of multimedia literary projects). I’m looking forward to the short story collection forthcoming from Rubén Degollado, which he has described as, “Friday Night Lights meets Macbeth.” Oh, and I recently blurbed the beautiful essay collection Funeral for Flaca by Emily Prado.

Kali Fajardo-Anstine is the author of the widely acclaimed Sabrina & Corina (One World, 2019), a finalist for the National Book Award, the PEN/Bingham Prize, The Clark Prize, The Story Prize, the Saroyan International Prize and winner of an American Book Award. She is the 2021 recipient of the biennial Addison M. Metcalf Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Fajardo-Anstine’s writing has been published in The New York Times, Harper’s Bazaar, ELLE, O the Oprah Magazine, The American Scholar, Boston Review, and elsewhere. Her stories are slated for translation in numerous languages including Japanese, Italian, German, Slovenian, Spanish, and Turkish.

Lily Philpott is an event producer and books enthusiast. She is a member of the International Literature Committee at the Brooklyn Book Festival, and a member of the advisory board of UK publisher And Other Stories. Born in Santiago, Chile, she lives and works in New York City.