Essential, Essential Workers

Leer en español.

If you take a savory food tour through Roosevelt, or Roosy for the ones that know, you’ll find that a lot of Mexican immigrants come from small towns all over the state of Puebla. And if they’re working in New York, it’s because they have to describe their hometowns by naming a bigger town 15 minutes away. My pops’ delivery route allowed him to connect with a piece of every little town in Puebla. This is Puebla York. His deafening laugh and inviting essence made the whole Hispanic strip seem like a united tribe.

–

In the ‘70s, the first Tellez brothers came to New York in search of opportunity, something that seemed impossible in our slow-paced town of Chila de la Sal. It’s a small town in Puebla between two larger towns: Xicotlán and Tulcingo del Valle. The Tellez family had been struggling to make ends meet for years. They would trade livestock across pueblos, however, each sibling had different aspirations and it was getting increasingly harder to support their families. So they decided to take a chance and move to Queens, where they started out working in factories and other low-wage jobs, saving up enough money to finally open their own businesses.

In the '80s,my mom and her sisters joined my grandpa in New York and found work at a family-owned Korean clothing factory in Sunnyside. By then, my dad was already working with his boys at a second factory, some from his hometown of Tilapa, and others from his time as a bartender in Mexico City. They shared a one-bedroom apartment in Woodside, where the sounds of cumbia chilanga and The Beatles echoed through the halls. Their pursuit for adventure led them to a club in Manhattan in 1991, where Sonora Dinamita were opening up for Los Bukis. I would come into the picture five years later, dancing to the same 4-count beat that brought my family together in the city that never sleeps.

From the 1990s to the early 2000s, New York’s Mexican population more than doubled—from 58,000 to around 187,000—concentrating in Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx, in that order. A heap of new faces forced to navigate culture, ideology, and above all, survival.

Through trial and error, my family learned to stabilize on the building blocks laid by our forebears. Tías and tíos were able to open their own businesses after working for their tío’s businesses all over Queens. I still remember the day when my mom took me to her job at Taco Veloz on 86th St., then owned by my tío Mingo. My cousin came over to visit and work on his drawing assignment. A Dominican patron saw what the borough oozes: potential. “Work hard and then the next day, work harder. That’s how you learn, that's how you grow. McDonalds started as a hamburger cart and now look, millions. Million dollar dreams baby, million dollar dreams!” We were being inspired, told we could reach for the stars if we wanted to…while my mother’s forearms were splattered by taco grease.

It doesn’t take much to find creativity in New York’s Mexican community. But for a young girl who could never assimilate to their Mexican or American side, we seemed so few and far between. I know we’re here…but where is our art? And why does it seem like the only places we can be together are the places in which we need to pray a certain way or be forced to spend money?

Growing up in what was then a mostly Greek, immigrant neighborhood, I felt the weight of being an outsider. Not from here, nor my parents' hometown—with neither side letting me forget it. I only felt fully welcome when we left Astoria and went to Roosevelt or Junction. And it wasn't until I started high school and began to explore Queens on my own terms that I found pockets of Latine culture that truly resonated with me. It was a revelation to see my culture (and South American cultures) represented and celebrated. It sparked a passion in me to expand my niche definition of Mexican-American.

–

Recently, Ashley Cervantes, a talented filmmaker and student, reached out via Instagram to ask me if I was interested in being a cumbia dancer for her independent thesis on Mexican-New York culture, El Remedio. I immediately accepted. In between takes, I connected with all the young POC creatives from similar backgrounds on that same feeling of disconnect. But it was in that studio where we realized there was no culture to aspire to be a part of because we were forming it ourselves. And now, as I see more cumbia events popping up throughout the five boroughs, Peso Pluma and Grupo Frontera dominating music charts, I feel hopeful that the next generation of Mexican-New Yorkers won't have to search as hard as I did to find a connection to their culture. Ashley, along with her dedicated team and our dispersed community, are a testament to our collective effort and the power of self-representation. I'm grateful to have been a part of it.

Because with each generation, the freedom to mold the culture based on creativity rather than survival opens up ever so slightly. We become more knowledgeable on pertinent rent, immigration, and labor laws that improve the quality of the community’s overall wellbeing. To put into perspective, the Chicano movement in the west became louder during the mid-1960’s and became key to mainstream Mexican representation in the US. It is why many of us can connect to classic Mexican-American movies like Stand and Deliver and Blood In Blood Out, but not fully relate. Their three-decade head start solidified their culture in the diaspora.

But New York is a different breed. The close proximity to Caribbean and African-American cultures has made an undeniable impact on Mexican youth. It permeates our language and consequently, everything we do (it must be said: Mexicans, please stop using the N-Word. It is not for us to bond over.) The differences in geography are a simple reason as to how New York Mexicans vastly differ from our family in California. There are barely any backyards we can hold bailes in, nor cultural centers that are securely funded. On the contrary, the price of eggs is now disrespectfully high and seems to become more of a luxury with each coming year.

–

As time progressed, rent grew higher, industries shifted, and New Yorkers had no choice but to work even harder. In 2010, my mom took on cleaning jobs, and my pops got hired by my tío Memo to distribute tortillas and other Mexican products to Queens, Brooklyn, and Manhattan. His internal alarm clock would wake him at 5am, and he’d get picked up by his best friend, Manny. He came home 12-14 hours later, physically fatigued, yelling Dominican slang Manny taught him that day while sitting down and processing his invoices, mentally exhausting him as well.

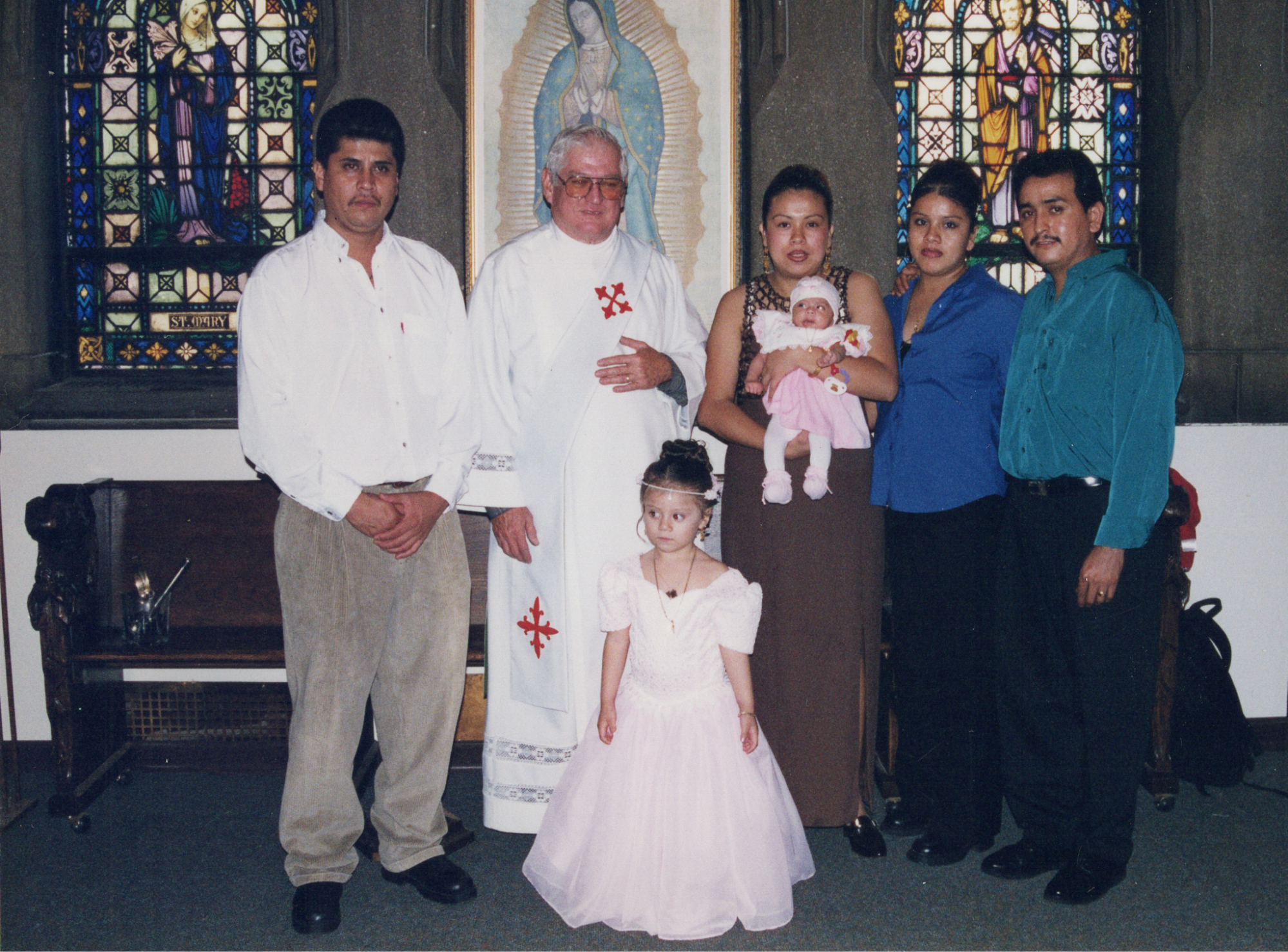

As if they didn’t have enough work, el señor y la señora Negrete ran a photography and film business on the weekends.They captured any family event they were hired for: quinceñeras, baptisms, weddings, etc. Their clientele was built on word of mouth, which naturally gifted them a strong social presence within the community. They knew whose tamales were good, whose pozole to avoid, and even became ‘padrinos de filmación’ to a client’s son.

As I strove to break into the competitive world of fashion, I often thought about the sacrifices my parents made for our family. I would sit at the kitchen table to study but wonder instead how tired my parents must be from working long hours just to make ends meet. It was a far cry from the life my family back in Mexico could have provided for me. My grandma didn't quite understand what I was studying, but that never mattered. What mattered was the unwavering support I received from my family - we were all in this together even while apart.

During the few weeks I would spend with my grandma every summer in Chila, we never talked about the future. Instead, we focused on cherishing the present. Climbing up a hill to buy Doña Chica’s famous bread, waking up at the crack of dawn to guard the calves so my grandpa and Tío Uri could milk the cows, going to la plaza to dance cumbia with my cousins. It was a grounding principle that would eventually help me find peace in the midst of constant work and hustle.

The cash flow of the small towns in Mexico made migrating inevitable. It’s what keeps parents and their parents apart. The melancholic side effect of leveling up is living far away from the ones you love. Working just enough to pay bills or gifting their children nice things is never enough. There were bills to pay in Mexico, too. Trading time for dollars, turning dollars into love, then avoiding turning that love into words. It’s the cycle many of our parents live. But when my grandma was hospitalized in 2019, dollars were obsolete. Our family had to strategize work schedules and hospital visitations as we were not able to freely visit her due to a contagious flu outbreak. Only then did they finally use their words. And unfortunately, they were to say goodbye.

Losing someone so vital to the family tree taught me that time is our most precious and fragile asset. In a world where hustle culture dominates, it's easy to get caught up in the race for success and forget to savor the little moments. Like when my pops would take my sister and I to the fish store just to look at the fish, time stood still and our breathing would sync up with the steady sound of the water. We would watch the fish, their bodies glistening in the light, and wonder if they ever got tired of swimming in circles. "Do the fishes ever get tired of their tanks, Pa?" I would ask. "Well, how would they know what a tank is?"

My dad would always make the effort to spend quality time with us. On Sundays, he’d pick a restaurant from his route and take us there to eat as a family. Almost every staff person greeted him like they grew up together back in Mexico. His familiarity and trust with the people of Queens was something so unique. So special. The way he genuinely connected with the people he worked with gave me solace that he wasn’t miserable while working. On the contrary, he made connecting with people his main job and then provided what their businesses needed. An essential, essential worker.

When the public grew more aware of this mysterious outbreak, no one knew what to do. Not the mayor, president, or even medical practitioners. NY1 told us that everyone should be working from home, save for essential workers. It was almost peaceful had there not been a high probability of death. We knew the people who would remain working were the people who always had to work.

One by one, starting with my pops, the household got sick. The news warned us not to go to the hospital until absolutely necessary. But what is necessary? And when could we go back to work?

My pops passed away on April 13, 2020 at 12:45am- the peak of the mortality rate in New York. Black and Brown New Yorkers were the most affected by the virus. The hardest thing for us to do leading up to his death was get him to stop working. He would rather continue to work and joke about how the people who stopped working during lockdown were “huevones” than take the opportunity to stay still. When he finally stopped going, he would continue taking calls and quantity requests from clients with that piercing volume in his jolly tone. “People still need to eat,” he would counter. There was no denying that.

As the hours progressed, his cough intervals grew shorter and shorter. “The route will always be there. Just rest,” my mom would tell him. Even when feverishly sleeping, he would sleep-talk about tortilla quantities and backing up the truck. It was funny at first, because of how vividly he spoke, until it was concerning.

–

“Hey! Where’s your dad? I haven’t seen him in a while!” Mr. Singh asked while pumping gas into what used to be my dad’s car. It’s a question we’d get asked often in Mexican restaurants where he used to deliver products. “Oh… he passed away. From Covid.” My family and I were shocked to see Mr. Singh shed tears. It brought us to tears, too, and gave us a powerful new memory of my dad. The idea of two men who formed a real connection through broken English and work routine was beautiful. We understood the love. We still feel it every time we visit my pops’ route.

One of my dad’s favorite restaurants, for example, was Delicias Puebla located at 89-04 Roosevelt Ave, whose tamales almost always sell out by 12pm. “What I like about that place is that there are actually women in the kitchen. That’s real home-cooked food,” he would say.

The familiar sights, sounds, and smells instantly bring back memories of the times we had all eaten there together as a family. As we left and thanked the staff, one of the restaurant’s runners, who my dad had always been friendly with, struck up a conversation. She asked how my dad was doing. I had to deliver the heartbreaking news. She was clearly sad, but not surprised. She had also recently experienced a loss due to COVID - her brother. We commiserate, sharing stories of the loved ones we had lost and the impact they had on our lives. It was a bittersweet moment. But I found comfort in the fact that my dad had left a positive impression on others and that his memory would live on beyond our family.

When May came around, an airy feeling in my palms became too much to bear. So I glued them to my keyboard and started applying to any jobs I had even the slightest interest in and reaching out to any clothing brands I could find the contact for. I couldn't help but feel like I was drowning in a sea of job applications and unanswered emails. My pops lost his mom and then his grandma at a very young age, I thought to myself. And I can't even find a job at 23? In New York? I must not be cut out for this life. But the truth was, I was just struggling to find my footing in a world that completely slowed down for everyone. Nothing in my small world made sense. Truth be told, what would have benefited me at the time, would have been finding community. Then I could have realized I was putting off grieving for a more convenient time. Truth be told, I’m still figuring it out.

Identity for me has always been a trivial concept. Rejecting the problematic ideologies of my community while still loving them has taught me a lot about the gray area. I think of it as my residence. I have witnessed the struggles and successes of all Latine-immigrant communities in the city. From small towns, our families have worked hard to make a life for themselves and future generations. However, the anxiety of hustle culture and the pressure to assimilate often overshadow our community building efforts. There is beauty in coming together as a united tribe, just like my pops did with his delivery route.

Mayte Negrete is a Fashion PR/Styling consultant based and raised in NYC. I build and execute press strategies for fashion brands as well as ideate and create content on set. My hobbies include playing around with Photoshop and video editing softwares. I’m motivated by the progression of people of color in the fashion industry. My vision is to build a bridge of knowledge to those in my community who feel that their dreams are out of reach. I’m a first-generation, first-born daughter; so I can do anything and everything. I really believe it.